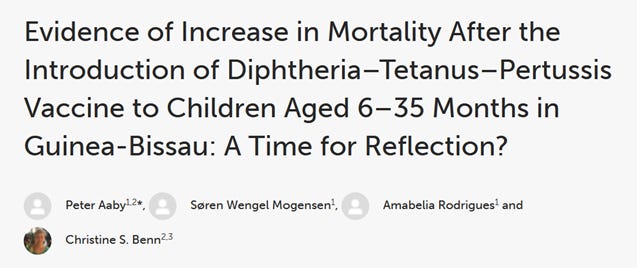

Vaccinologists Do Not Entirely Understand What Vaccines Are Doing: A Closer Look at Non-Specific Effects, Especially Population-Level Adverse Events

Co-administration of vaccines and the order in which vaccines are given may result in population-level adverse events.

JOIN OUR NEW MEMBERSHIP ORG; WORLD SOCIETY FOR ETHICAL SCIENCE (ipak-edu.org) and drive ethical, objective science forward.

Vaccines are lauded as monumental achievements including the prevention of myriad deadly diseases. Yet, a full command of the available research shows that the impact of vaccines transcends their primary preventive roles, challenging the foundational understanding held by vaccinologists. The evidence is strong that vaccine-induced non-specific effects (NSEs), which we will rechristen “population-level adverse events (PLAEs)”, to enhance a full comprehension of immunization-related non-specific events.

Discovery of Population-Level Adverse Events (PLAEs)

The exploration of these problems began with observations by the Bandim Health Project in Guinea-Bissau, under the guidance of Professor Peter Aaby. In the 1980s, Aaby's team initially found that the measles vaccine significantly reduced child mortality beyond just preventing measles. This discovery led to broader investigations, revealing vaccines' complex impacts on the immune system and overall health.

Live vs. Non-Live Vaccines: A Dichotomy of Effects

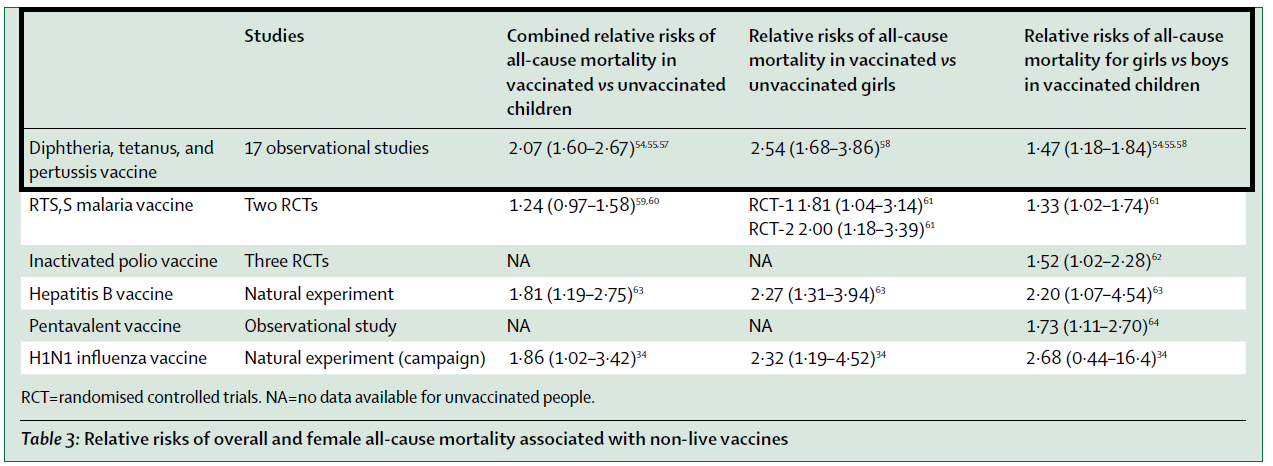

Subsequent studies distinguished between the NSEs of live and non-live vaccines. Live attenuated vaccines, such as Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), measles, and oral polio vaccines, were linked to beneficial NSEs, including mortality reductions from non-targeted infections. Conversely, non-live vaccines, notably the whole-cell diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP) vaccine, were associated with negative NSEs, that i.e., PLAEs particularly in females, leading to increased mortality rates.

The DTP Vaccine Risk Signal

The DTP vaccine's PLAEs, or negative NSEs, have sparked significant interest in the vaccine risk-aware community. Research has consistently showed that vaccinated girls had higher mortality rates than unvaccinated peers. For instance, a study cited in the critique revealed that receiving the DTP vaccine was associated with a 2.07 (95% CI=1.60-2.67) times higher mortality, with the effect being more pronounced in females, showing a 2.54 (95% CI=1.68-3.86) times increase. These findings underscore the urgency for a reevaluation of vaccine schedules, in particular the question of the order of vaccines as a risk factor for PLAEs.

In a LINKEDIN article, one of the study group members, Christine Stabell Benn, summarized the history:

“This led to an investigation of all the childhood vaccines. Unknown to most people, the childhood vaccines were never investigated for their effects on other infections, just the target infections(s). We discovered that all the vaccines we studied had NSEs.

A pattern emerged. All the live vaccines we studied had beneficial NSEs. However, for DTP vaccine, a non-live vaccine, we consistently found the vaccine to be associated with negative NSEs, particularly for girls. Hence, despite being protected against three deadly diseases, girls who received DTP vaccine had higher risk of dying than girls, who did not receive DTP vaccine, and DTP-vaccinated girls had higher risk of dying than DTP-vaccinated boys, even though the opposite was the case after live vaccines.

We went to WHO with this worrying safety signal. In the first place, WHO commissioned some other sites to test our findings. These studies came out with extremely positive effects of DTP vaccine. However, they had used a flawed methodology, something that was acknowledged in 2006, and led WHO to declare that they would "keep a watch on the evidence of non-specific effects of vaccination".

Studies showing non-specific effects of vaccines continued to accumulate and in 2013, WHO’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) established a working group on the non-specific effects of vaccines and conducted a review of the NSEs of the live measles and BCG vaccines and the non-live DTP vaccine. The review was published in BMJ in 2016. A total of 10 DTP studies were included in the analysis. While the two live vaccines were observed to reduce overall mortality much more than explained by the prevention of the target diseases, it was opposite for DTP vaccine, for which the reviewers concluded that “Receipt of DTP (almost always with oral polio vaccine) was associated possible increase in all cause mortality on average (relative risk 1.38, 0.92 to 2.08) from 10 studies at high risk of bias; this effect seemed stronger in girls than in boys”. Receiving measles vaccine or BCG vaccine with of after DTP vaccine was associated with lower mortality than having DTP as the most recent vaccine. The reviewers recommended that the evidence “does indicate a need for randomised trials to examine the positioning of DTP in the vaccine schedule”.

At their meeting in April 2014, WHO’s SAGE tasked the committee IVIR-AC with defining the research questions to be studied in relation to NSEs. However, no studies in relation to DTP have apparently been planned, now almost 10 years after the meeting.

After the WHO review, we went back to the old records. BHP had introduced DTP vaccine in the community in the 1980s, believing it to be beneficial. However, when we got the data entered and analysed, we found further confirmation of negative NSEs of DTP vaccine. The best data was in the 3-5-month-old children, because in this age group, since DTP vaccine was given at 3-monthly weighing sessions, it was completely random (dependent on the birth date) if a child was vaccinated or not.

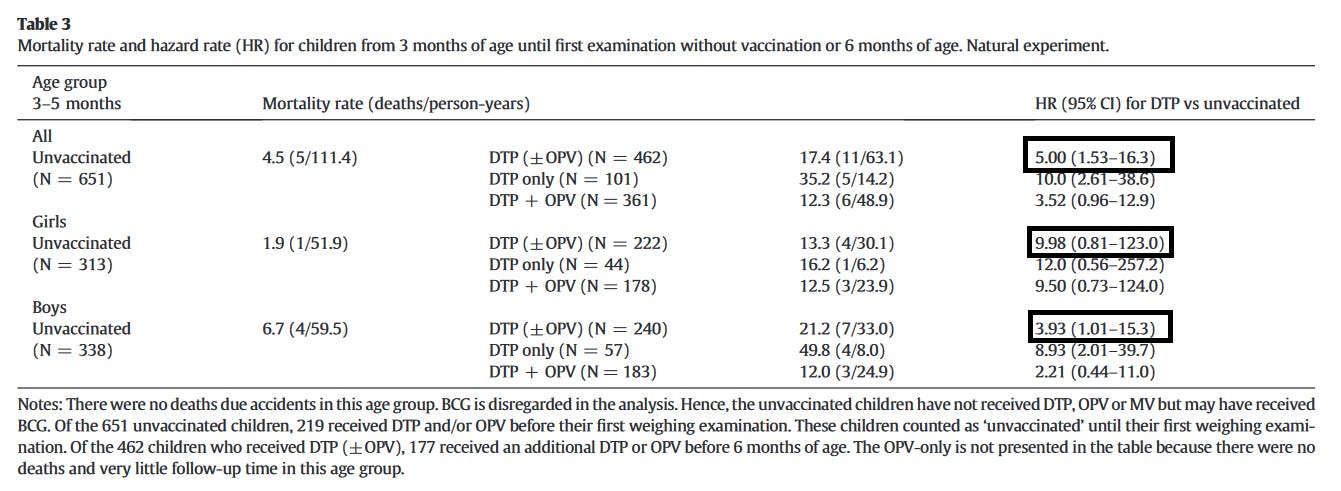

In this “natural experiment” covering data from 1981-83, children, who received DTP vaccine had 5 times higher mortality than children who had not yet received DTP vaccine. This was more pronounced for females (10 times higher) than for males, but the result did not reach significance.

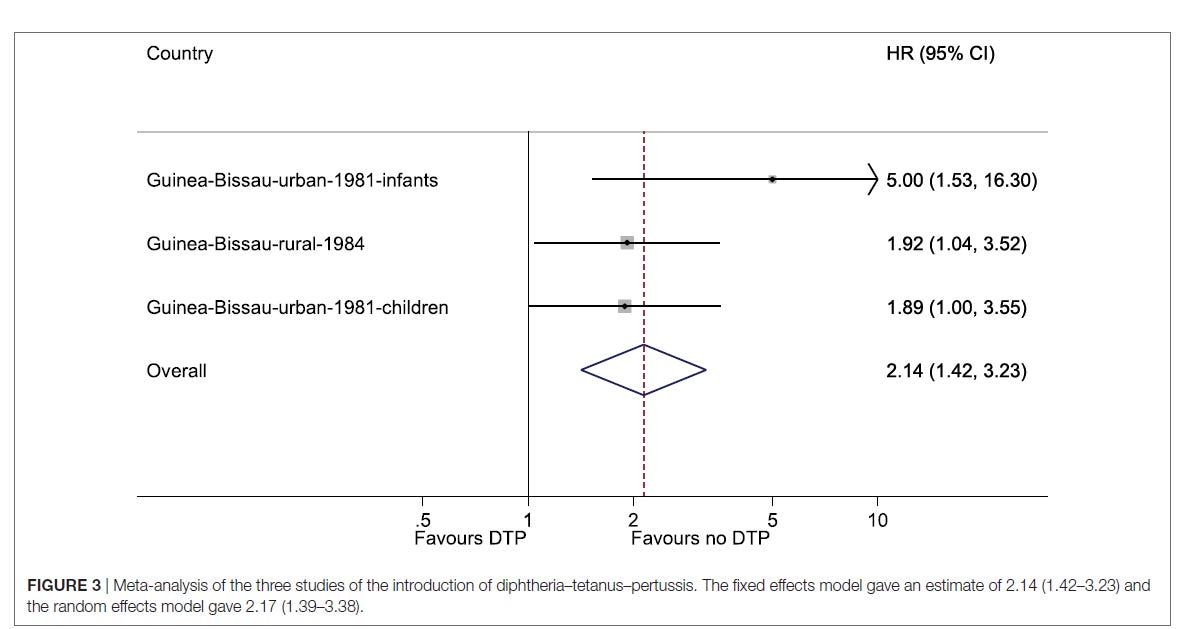

In subsequent studies of older children in the same period, we found similar results, and in 2018 we published a combined analysis of the three studies conducted during the introduction.

The analysis showed that the introduction of DTP vaccine in Guinea-Bissau was associated with a 2-fold increase in overall mortality. In girls, the estimate was a 2.60 (95% CI=1.57–4.32)-fold increase in mortality. Noteworthy, these studies were published after the WHO review. Had they been included in the WHO review, the negative effect of DTP vaccine would have been stronger.

In 2020, we reviewed all the data, in connection with a major review of the non-specific effects. Including all the studies with prospective follow-up, also the new studies, for a total of 17 studies, being DTP vaccinated vs. not being DTP vaccinated was associated with 2.07 (95% CI=1.60-2.67)-fold higher mortality. The estimate was 2.54 (1.68-3.86) in females. Among DTP-vaccinated children, females had almost 50% higher mortality than males (1.47 (1.18-1.84)). A dose-response has been observed, with the female-male mortality ratio increasing with each additional dose of DTP vaccine.

DTP is not the only vaccine that is associated with increased overall female mortality. The same pattern has been seen for now six non-live vaccines (See the table below). Importantly, the opposite pattern is seen for live vaccines. They are associated with beneficial NSEs and decreased overall mortality, particularly for females. No bias can explain why only non-live vaccines should be negative for females.

Importantly, since the data shows that the negative effect is abrogate when a live vaccine is given, it should be possible to design vaccination programs that include the important non-live vaccines that protect against deadly diseases, but just make sure that children spend as much time as possible with a ”live-vaccine-last”.

One of our DTP studies was a recent analysis of the "natural experiment" that took place when DTP vaccine was introduced in Guinea-Bissau 30 years ago. It showed that receiving DTP vaccine vs. not yet receiving DTP vaccine was associated with 5-fold significantly higher mortality. It was 10-fold higher for females, but it was not independently significant for girls.

However, this is just one of many studies of DTP vaccine that all point in this direction. Most of them are from Guinea-Bissau, but the findings have been the same in e.g., Benin, India and Malawi.

The conclusion is very clear: The whole-cell DTP vaccine used in low-income countries is associated with increased mortality for females. The observation has not been contradicted by good prospective studies. What remains unclear is why WHO does not act.

Below follows a list of some of the studies showing negative non-specific effects of DTP vaccine in females. No good study of DTP given without BCG and with prospective follow-up has contradicted the findings.”

WHO's Response and Inaction

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized the potential importance of NSEs, establishing a working group to review the evidence. Despite this, nearly a decade has passed without significant action to address the concerns raised by these findings. The delay highlights a gap in our understanding and application of vaccine science.

The Path Forward

The evidence of NSEs underscores the need for a paradigm shift in vaccine testing, approval, and administration. Vaccinologists and public health officials must consider vaccination's broader implications. Optimizing vaccine schedules, such as ensuring live vaccines are administered last, could enhance the overall health benefits of immunization programs.

The investigation into non-specific effects, especially PLAEs of vaccines reveals a complex interaction between immunization and the immune system, suggesting a partial understanding by vaccinologists of vaccines' full impact. We need answers, especially on the question of adverse events from co-administered vaccines in all countries.

The global health community must remain open to reevaluating assumptions about vaccines, guided by the principle of maximizing overall health outcomes, not robotically pushing vaccines as a panacea for infectious diseases.

References:

Kristensen I, et al. Routine vaccinations and child survival: follow up study in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. BMJ 2000;321:1435–8.

Aaby P, et al. Routine vaccinations and child survival in war situation with high mortality: effect of gender. Vaccine 2002;21:15–20.

Aaby P, et al. Differences in female-male mortality after high-titre measles vaccine and association with subsequent vaccination with diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis and inactivated poliovirus: re-analysis of West African studies. Lancet 2003;361:2183–8.

Aaby P, et al. The introduction of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine and child mortality in rural Guinea-Bissau: an observational study. Int J Epidemiol 2004; 33: 374–80.

Aaby P, et al. Divergent female-male mortality ratios associated with different routine vaccinations among female-male twin pairs. Int J Epidemiol 2004; 33:367–73.

Veirum JE, et al. Routine vaccinations associated with divergent effects on female and male mortality at the paediatric ward in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau. Vaccine 2005; 23: 1197-204

Aaby P, et al. Sex differential effects of routine immunizations and childhood survival in rural Malawi. Pediatr Inf Dis J 2006;25:721–7.

Aaby P, et al. Age-specific changes in the female-male mortality ratio related to the pattern of vaccinations: an observational study from rural Gambia. Vaccine 2006; 24:4701–

Aaby P, et al. Increased female-male mortality ratio associated with inactivated polio and diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccines: Observations from vaccination trials in Guinea-Bissau. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2007; 26: 247-52.

Aaby P, et al. DTP with or after measles vaccination is associated with increased in-hospital mortality in Guinea-Bissau. Vaccine 2007; 25: 1265-9

Benn CS, et al. Why worry: vitamin A with DTP vaccine? Vaccine 2007; 25:777–9.

Benn CS, et al. Does vitamin A supplementation interact with routine vaccinations? An analysis of the Ghana vitamin A supplementation trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 90:629–39.

Aaby P, et al. Early diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccination associated with higher female mortality and no difference in male mortality in a cohort of low birthweight children: an observational study within a randomised trial. Arch Dis Child 2012:97:685–91

Benn CS, et al. Diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccination administered after measles vaccine: Increased female mortality? Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2012; 31: 1095-7.

Aaby P, et al. Testing the hypothesis that diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine has negative non-specific and sex-differential effects on child survival in high-mortality countries. BMJ Open 2012; 2:e000707.

Hirve S, et al.. Non-specific and sex-differential effects of vaccinations on child survival in rural western India. Vaccine 2012;30:7300–8.

Krishnan A, et al.. Non-specific sex-differential effect of DTP vaccination may partially explain the excess girl child mortality in Ballabgarh, India. Trop Med Int Health 2013;18:1329–37

Aaby P, et al. Sex-differential and non-targeted effects of routine vaccinations in a rural area with low vaccination coverage: Observational study from Senegal. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg 2015;109:77–85.

Higgins JPT, et al. Association of BCG, DTP, and measles containing vaccines with childhood mortality: systematic review. BMJ 2016;355:i5170.

Aaby P, et al. The WHO review of the possible nonspecific effects of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2016; 35: 1247–57.

Aaby P, et al. Is diphtheria-tetanus- pertussis (DTP) associated with increased female mortality? A meta-analysis testing the hypotheses of sex-differential non-specific effects of DTP vaccine. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2016; 110: 570–81

Aaby P, Ravn H, Benn CS, et al. Child mortality after inactivated vaccines versus standard measles vaccine at nine months of age: a combined analysis of five cross-over randomised trials. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2016; 35:1232–41.

Andersen A, et al. Sex-differential effects of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine for the outcome of paediatric admissions? A hospital based observational study from Guinea-Bissau. Vaccine 2017; 35:7018–25

Welaga P, et al. Fewer out-of-sequence vaccinations and reduction of child mortality in Northern Ghana. Vaccine 2017; 35:2496–503.

Mogensen SW, et al The introduction of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis and oral polio vaccine among young infants in an urban African community: a natural experiment. EBioMedicine 2017; 17: 192–98.

Aaby P, et al. Evidence of increase in mortality after the introduction of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine to children aged 6–35 months in Guinea-Bissau: a time for reflection? Front Public Health 2018; 6: 79.

Hanifi SMA, et al. Diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP) vaccine is associated with increased female-male mortality rate ratios. A meta-analysis of studies of DTP administered before and after measles vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2020 Oct 30.

Clipet-Jensen C, et al. Out-of-Sequence Vaccinations With Measles Vaccine and Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis Vaccine: A Reanalysis of Demographic Surveillance Data From Rural Bangladesh. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 Apr 26;72(8):1429-1436

Øland CB, et al. Reduced Mortality After Oral Polio Vaccination and Increased Mortality After Diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis Vaccination in Children in a Low-income Setting. Clin Ther. 2021 Jan;43(1):172-184.e7

Jack

But please note when I asked Benn about neurological complications of vaccines (autism etc) she confessed they’d never studied it.

https://www.ageofautism.com/2020/07/no-data-for-neurological-impairment.html

Is it a "flawed methodology" or is it cover for a criminal enterprise?