Update to the IPAK BigQuery Data Resource of HHS Medicare Data

How to access. Updates to full annotation. Hints at justifiably robust analysis. Encouragement to stick with it. Caveats on interpretation.

Overview of the Medicaid Provider Spending Data

The dataset provides a comprehensive view of Medicaid payments and service volumes across the United States. It captures the intersection of healthcare providers, specific medical procedures (HCPCS codes, NOT ICD-10 codes), and time.

Key Data Components:

Identifiers: National Provider Identifier (NPI) for both billing and servicing providers. The are cross-referenced to 2/2026 NPI names (also from HHS).

Procedures: HCPCS codes representing the specific medical services rendered.

Timeframe: Monthly granularity (

CLAIM_FROM_MONTH) currently spanning from January 2018 to December 2024.Volume Metrics: Total unique beneficiaries served and total number of claims submitted.

Financial Metrics: Total amount paid for services.

Queries Over Time

Analysis over time allows us to see how healthcare spending and utilization evolve. Common time-series queries include:

Spending Growth Trends: Tracking how total Medicaid outlays change year-over-year.

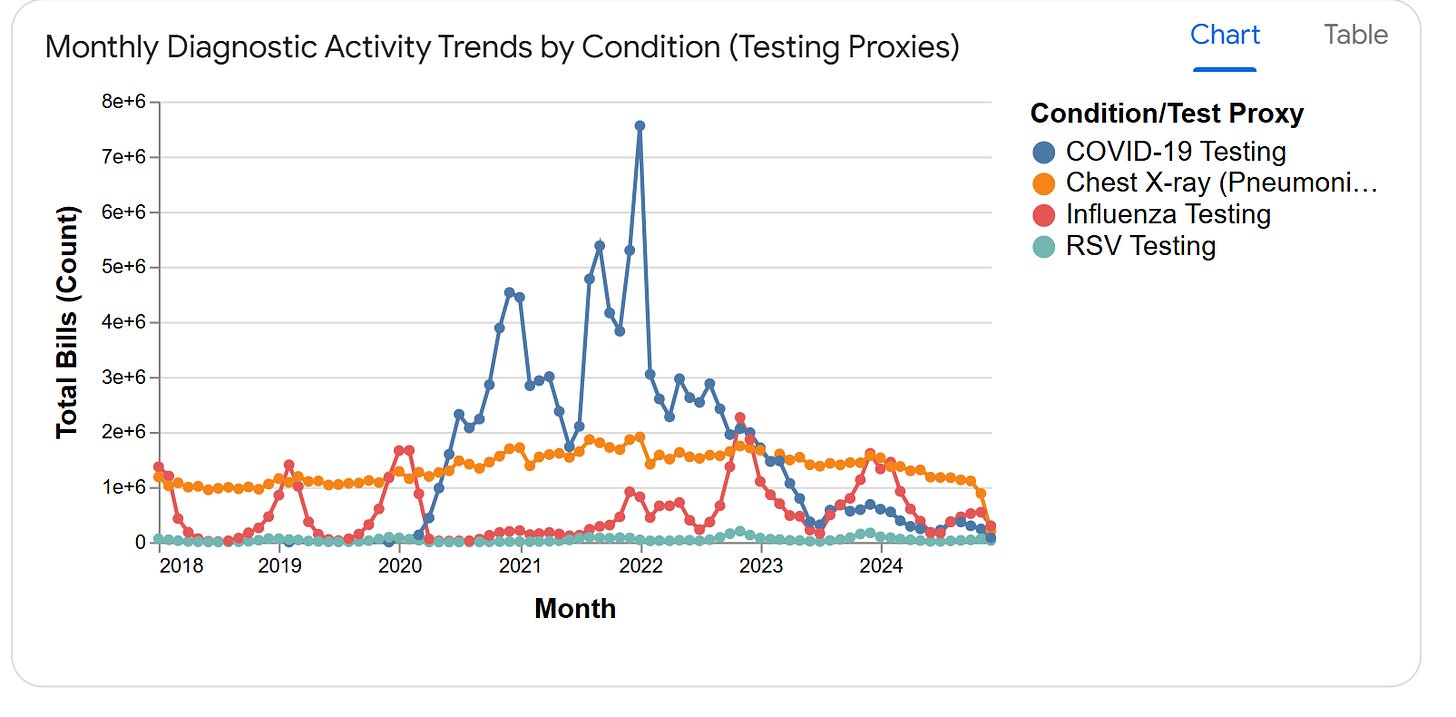

Seasonality Analysis: Identifying certain months (like the end-of-year or peak flu seasons) where specific HCPCS codes see higher claim volumes.

Impact Analysis: Visualizing the effect of external events, such as the significant dip in claims and spending observed in early 2020 during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

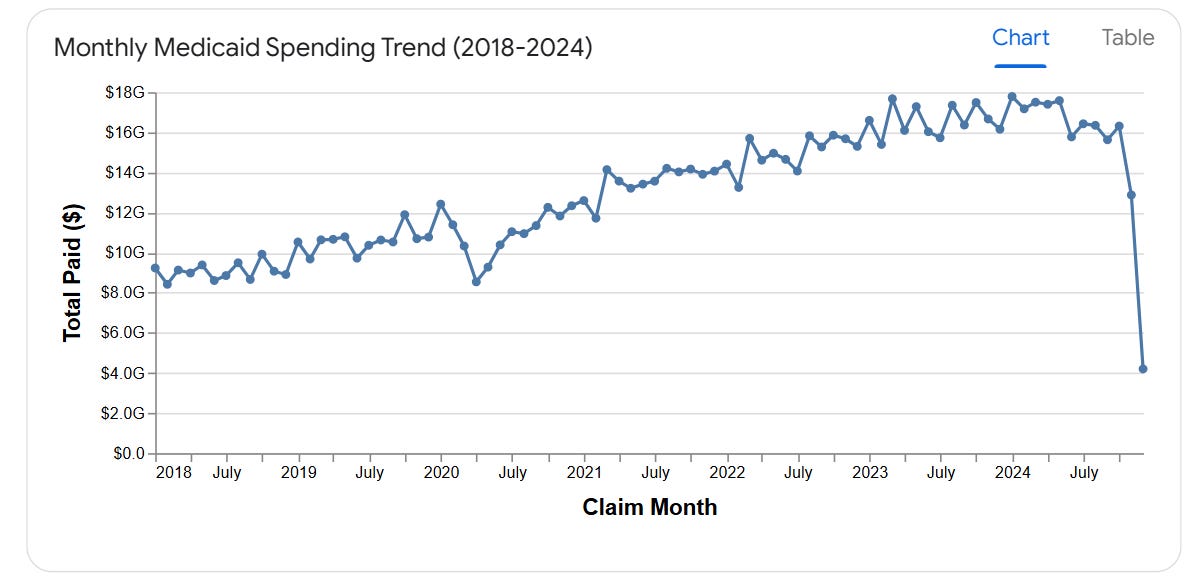

The chart below illustrates the monthly spending trend, showing a steady rise in Medicaid payments from roughly $9B per month in 2018 to over $17B per month in early 2024.

“Justifiably Robust” Data Analysis Requests

A “justifiably robust” request goes beyond simple surface-level totals. It involves deep dives into efficiency, provider behavior, and predictive insights. Robust requests typically include:

Efficiency Metrics: “Calculate the average cost per beneficiary for HCPCS code 99213 (Office Visit) across all billing providers binned by size (number of unique beneficiaries) and practice type (specialty vs. general) to identify cost outliers.”

Behavioral Shifts: “Find providers whose claim volume grew by more than 50% in a single quarter compared to their 2-year historical average.”

Predictive Modeling: “Using the last 3 years of data, forecast the expected Medicaid spending for the next 6 months to assist with state budgeting.”

Procedure Concentration: “Which 5 HCPCS codes account for the top 50% of total spending, and how has that concentration shifted over the last 5 years?”

Insights

Total Scale: The dataset captures over $1.09 Trillion in spending across nearly 19 Billion claims, making it a massive source for public health and economic research.

Steady Growth: There is a clear upward trajectory in both spending and claims, with monthly payments nearly doubling over the 7-year period.

Pandemic Volatility: The data clearly reflects the healthcare disruption in 2020, with a sharp decline in claims during the initial lockdown period followed by a significant rebound.

Risky/Reckless Analyses

1. The “Data Lag” Fallacy (Reporting on Recent Months)

The most common reckless analysis is reporting a “massive decline” in recent spending without accounting for claim “run-out” (the time it takes for claims to be processed and reported).

Looking at the data below, a reckless analyst might report that Medicaid spending “crashed” by 75% in December 2024. In reality, the data for that month is simply incomplete.

2. The “NPI Generalization” Risk

As noted in the data description, NPIs are not always standard. Treating the “A” or “M” prefixed identifiers (which appear in millions of records) as standard 10-digit NPIs during a join to external registries will lead to massive data loss and skewed results. A reckless analysis would ignore these “atypical” providers, potentially missing billions in spending concentrated in specific state-managed programs.

3. “Global Averaging” (The Mixed-Bag Metric)

Calculating a “Global Average Payment per Claim” across the entire dataset is a methodologically bankrupt exercise. Because HCPCS codes range from low-cost laboratory tests ($10) to complex surgical procedures ($10,000+), a global average tells you nothing about efficiency.

For instance, the query below shows how vastly different the “average” is depending on the procedure. Reporting a single average for a provider who performs both is reckless.

Insights on Reckless Analysis

Ignoring Run-out: Any analysis of the most recent 3-6 months of Medicaid data is inherently “risky” because of varying reporting speeds across different states and providers.

Identifier Misuse: Attempting to determine the “specialty” or “location” of a provider based only on the

medicaid_provider_spending_rawtable is impossible on this platform alone, as these attributes are not in the raw data and require a specific, careful join.Volume vs. Value: Ranking providers solely by

TOTAL_PAIDwithout looking atTOTAL_UNIQUE_BENEFICIARIESis reckless; a provider with high spending might simply be a large hospital system serving thousands, not an “expensive” outlier.

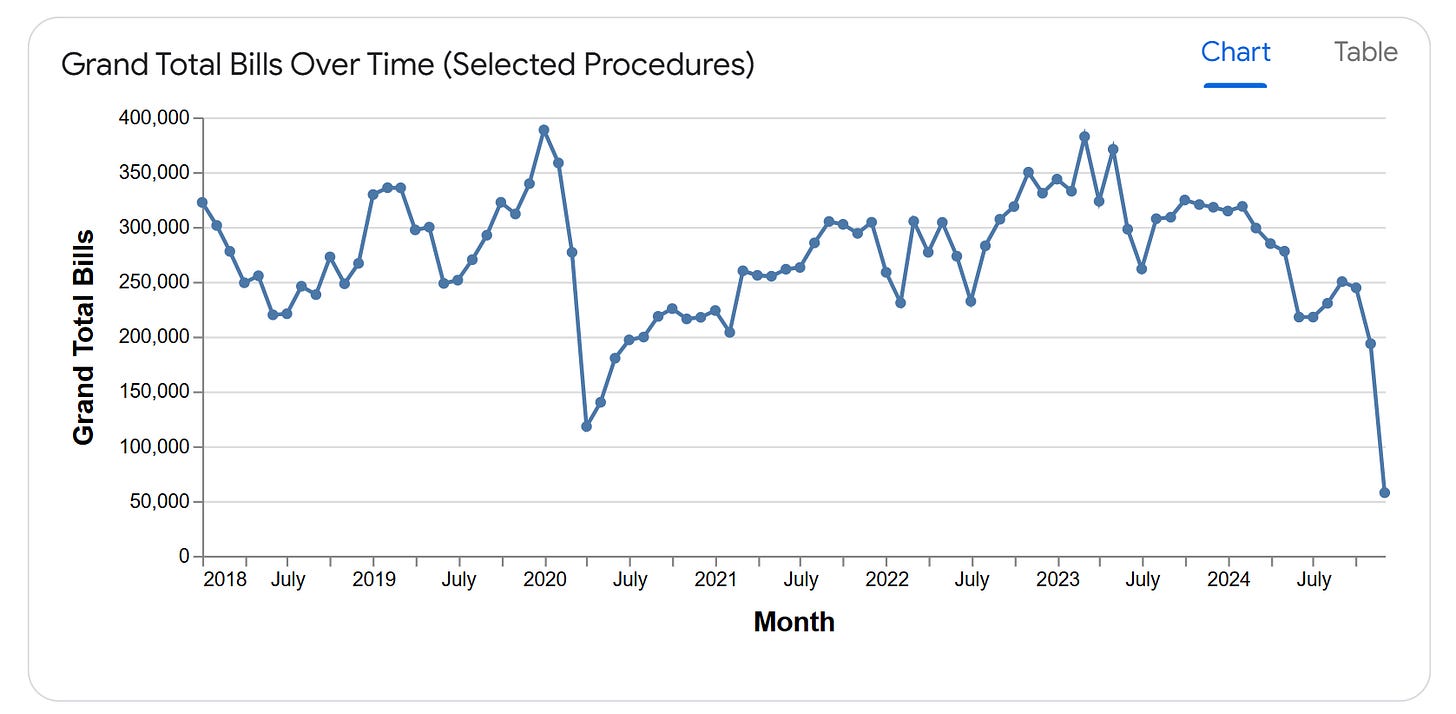

Here’s an example of data run-out at the end of 2024:

These are the Grand Total # of Bills in hospitals for a collection of procedures related to the detection and treatment of bacterial pneumonia. The run-out at the end of the series is an artefact; hospitals stopping standard care for bacterial pneumonia in March and April of 2020 is likely real due to lock-step following of COVID-19 protocols. Ironically, the dataset-wide peak just prior to COVID-19 was unlikely attempts to understand the new cases of pneumonia without any guide due to the delay in reporting of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and NCoV-19 (not COVID-19) pneumonia.

Other Caveats

Fraud cannot be proven by high-level monthly record analysis alone. Variation in specialty explains a lot of variation among practices. Currently the data are available as unparsed, parsed into pediatric and non-pediatric, and cancer- and non-cancer treating NPIs. These steps were achieved using SQL and Gemini, so any inexactitudes imposed by those systems are present when asking the system to use the available bipartitions.

Running the same exact queries multiple times to make sure you see the exact same results is essential.

Leaving it to the authorities (CMS, OIG, FBI, DEA) to follow-up on suspected fraud is by far more responsible than trying to publish about any particular NPI without knowing the facts or exceptions. You may wish to report your findings, but be clear in your role: You are posing POSSIBLE, not even LIKELY problems.

All results from AI must be confirmed by off-system analyses.

The rest is up to you. IPAK, IPAK-EDU LLC and James Lyons-Weiler make no warranty or guarantee on the precision and accuracy of your results.

If you have questions about the data, or policy changes leading to the data release, contact HHS.

PS It helps to screenshot your attempts to access and ask ChatGPT to help you set up access. It is not perfect, but it helps. Keep trying.

Rewards are offered for discovering cases of Medicare/Medicaid fraud. A database has been made available by the HHS Secretary so that the public can do searches. IPAK has made searching it easier. (See Popular Rationalism substack for instructions.)

I had a brush with a possible case of Medicare/Medicaid this week as my 87+ year old mom was admitted to a facility, after an ordinary fall, for "rehabilitation" in Texas.

I'm tempted to try to query this newly available database to find out if the same pattern of behavior is going on at facilities across the country. But I don't have the motivation to take on the task. I might if others want to figure out the best way to query the data to get results.

My sister, who took her to the ER, was referred to rehab, even though ER didn't treat her for anything other than ice on the bruise. The sales rep from the facility gave my sister the hard sell and guilt trip: "You can't leave your mother alone. She needs 24 hour care!"

The plan that we chose for her to improve balance was: lots of exercise, lots of rest and healthy food. No medications. Other than assistance needed going to the bathroom in the middle of the night, my mom is capable of feeding and dressing herself and taking care of most personal needs.

Without our knowledge and against our instructions, she was immediately given pain killers and trazodone, which has a number of side effects, including sleepiness and increased risk of falling. When my sister dropped in for a visit, she found her, dozing off during "exercise" sessions strapped into a wheelchair. Otherwise, she was confined to a bed that had a loud alarm that prevented her from getting up. Not even to go to the restroom. We had specifically said "no bed alarm" in our plan. Our mom was traumatized. My sister took her back home. The facility is Encompass which has locations throughout the country.

Things like this happen to families every day. We seldom feel like we have to power to do anything about it. Nor do we bother because Medicare/Medicaid is paying the bill.

And they were just "following protocol." I suspect that when my sister brought her in, she was asked to sign a bunch of papers that gave them permission to treat as they thought necessary, despite the fact that we had made a detailed plan with the director (of marketing?).

Probably, they have the routine down that protects them from accusations of breaking the law or abuse. But the fact remains, I think, that my mom wasn't eligible for "rehabilitation" to begin with since she wasn't injured. Whatever care they gave her and charged to Medicare/Medicaid was unnecessary, as well as damaging. I wonder if anyone else has had similar experiences with "rehab" centers for the elderly.