IPAK Publishes Fully Queryable HHS Medicaid Provider Spending Archive Is Now Public. Unfettered, PERMANENT Access.

Transparency without friction is the only meaningful transparency. We spent the day making this available so EVERYONE can query the data with typed prompts, not codes.

Be careful your results are not positively misleading. Use best practices to avoid misleading results- and consider consulting with someone who understands data analytics!

Today, an unmodified archival copy of the HHS Medicaid Provider Spending dataset has been published as a public IPAK BigQuery HHS dataset. It is queryable by anyone with a Google account. No scraping. No downloads required. No proprietary gatekeeping.

This is the raw file, ingested directly from the official HHS Open Data release. No transformations. No filtering. No derived fields. The ingestion artifact is cryptographically anchored via SHA256 for integrity verification.

Below is exactly how to access it and find providers contained in the results.

What This Dataset Contains

This dataset includes provider-level Medicaid spending aggregated by:

Billing Provider NPI

Servicing Provider NPI

HCPCS procedure code

Month of service

Total unique beneficiaries

Total claims

Total paid amount

Each row represents a provider–procedure–month aggregation.

Source:

HHS Open Data Portal — Medicaid Provider Spending (T-MSIS derived)

BEGINNER GUIDE

How Anyone Can Query the Data (Step-by-Step)

You do not need to download anything.

You do not need to install software.

You only need a free Google account.

Step 1 — Create a Google Account (If You Don’t Have One)

Go to:

https://accounts.google.com/signup

Create a free account.

Step 2 — Open BigQuery

Visit:

https://console.cloud.google.com/bigquery

If prompted:

Accept terms

Select your account

You do not need to enable billing to query public datasets.

Step 3 — Open the Public Dataset

In the search bar, paste:

project-401c8f7e-90fc-4838-9fc.medicaidproviderspending_1771078072347.medicaid_provider_spending_rawClick the table.

You can now:

View schema

View sample rows

Run queries

Step 4 — Using Gemini to Query

Click the “Create conversation” button (or open the Gemini panel if visible).

Now you can ask questions in plain English.

Examples:

What is the total Medicaid spending in this dataset?

Show the top 25 billing providers by total paid amount.

Which HCPCS codes account for the highest total spending?

Show monthly spending trends over time.

Which providers had the largest increase in spending year over year?

Gemini will generate and run the query for you.

You can see the SQL it generates before execution.

If it looks correct, click Run.

Step 5 — Further Use Gemini to Explore

Identifying Practices Billing More Than 2 Standard Deviations Above Peers

If you want to identify unusually high billing patterns — in a statistically defensible way — you can ask Gemini to compute outliers relative to peer distributions.

We will do this in three structured steps.

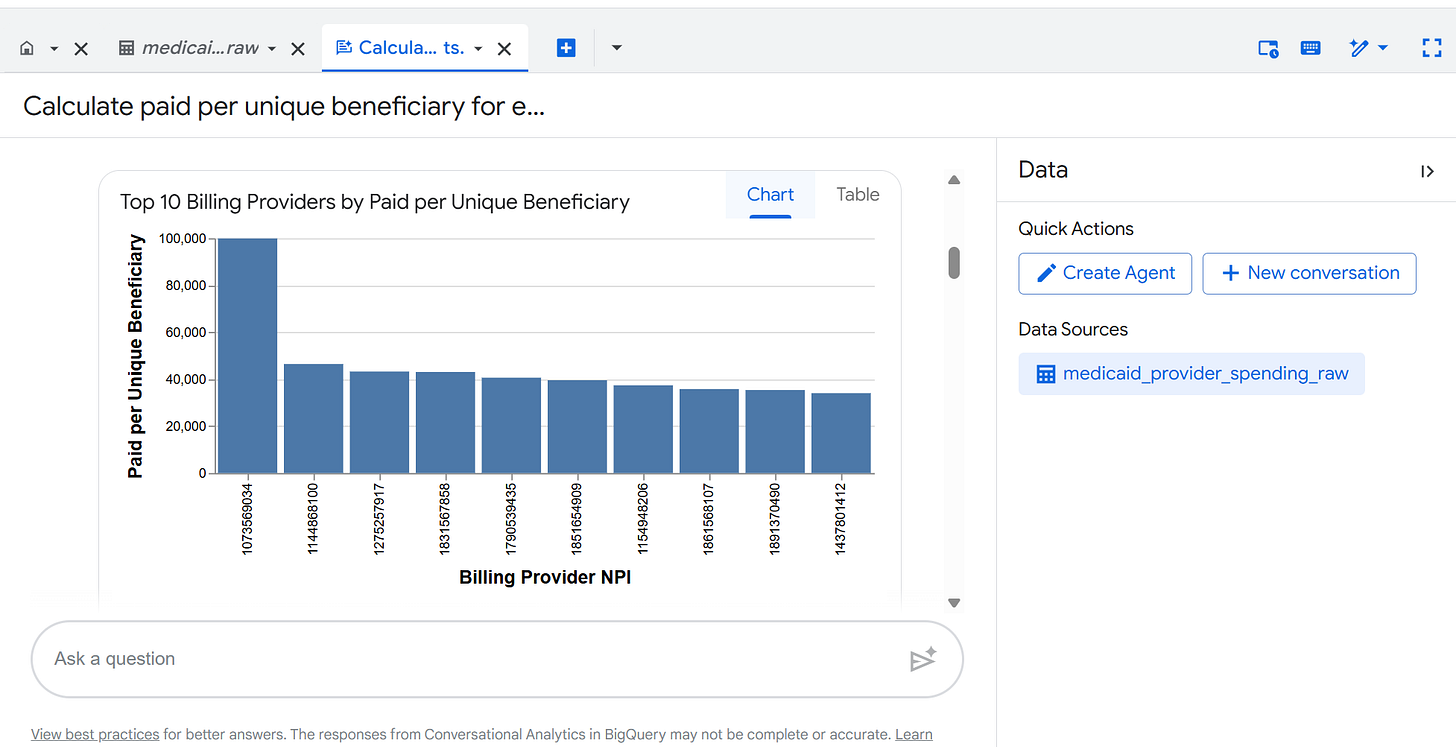

Step 5A — First Ask Gemini to Compute Paid Per Beneficiary

In the Gemini prompt box, type:

Calculate paid per unique beneficiary for each billing provider, defined as SUM(TOTAL_PAID) divided by SUM(TOTAL_UNIQUE_BENEFICIARIES). Return provider-level results.

This creates a normalized metric:

Paid per unique beneficiary

= Total paid ÷ Total unique beneficiaries

Normalization matters.

Raw totals alone are not meaningful comparisons.

Review the generated SQL before running it.

Step 5B — Ask Gemini to Calculate the Mean and Standard Deviation

Now type:

Calculate the mean and standard deviation of paid per unique beneficiary across all billing providers.

This establishes the baseline distribution.

Gemini will compute:

Average paid per beneficiary

Standard deviation of paid per beneficiary

These values define what “normal” looks like in the dataset.

Step 5C — Identify Providers More Than 2 Standard Deviations Above the Mean

Now type:

Identify billing providers whose paid per unique beneficiary is more than 2 standard deviations above the mean. Return provider ID, paid per beneficiary, and number of beneficiaries.

This flags providers whose per-beneficiary billing intensity is statistically elevated.

2 standard deviations above the mean is a common threshold for identifying unusually high values in a distribution.

Step 5D - Identify the Providers from their NPIs

HHS has an NPI registry here: https://npiregistry.cms.hhs.gov/search

Why This Method Matters

You are not asking:

“Who looks high?”

You are asking:

“Who exceeds a statistically defined threshold relative to peers?”

That distinction matters.

Important Interpretation Cautions

• High paid per beneficiary does not automatically indicate wrongdoing.

• Some specialties serve higher-acuity populations.

• Procedure mix can distort comparisons.

• Month aggregation may mask episodic spikes.

This is a screening tool, not a conclusion.

Optional Refinement

You can further constrain the comparison:

Perform the 2 standard deviation analysis within each HCPCS_CODE separately.

Or:

Perform the 2 standard deviation analysis within each CLAIM_FROM_MONTH.

This compares providers against true procedural peers.

CAVEAT ON INTERPRETATION:

Ranking providers by total paid without context is analytically weak because raw totals conflate scale with intensity. A more defensible approach is to first bin providers by total number of unique beneficiaries, creating peer groups of similar size, and then rank providers within those bins on normalized metrics such as paid per beneficiary or paid per claim. For example, providers can be grouped into strata (e.g., 1–50 beneficiaries, 51–250, 251–1,000, 1,001–5,000, 5,000+). Within each stratum, variation in total paid reflects differences in billing intensity or service mix rather than mere population size. This reduces scale bias and prevents large multi-site systems from being mechanically ranked above small specialty practices simply because they serve more patients. Stratified ranking transforms the question from “Who bills the most?” to “Who bills more than similarly sized peers?” — a far more meaningful starting point for anomaly detection or policy analysis.

Step 6 — Export Results

You can:

Download results as CSV

Copy results

Share query links

You are running queries under your own Google account. Query costs apply to your account if you exceed free limits.

For Journalists and Analysts

This dataset is:

Public

Immutable (read-only)

Cryptographically anchored

Fully reproducible

You can independently verify totals and trends.

VERSION 2

Expert Access Guide

For analysts, data scientists, and auditors.

Dataset Path

project-401c8f7e-90fc-4838-9fc.medicaidproviderspending_1771078072347.medicaid_provider_spending_rawRegion: US

Access: Public read-only (allAuthenticatedUsers → BigQuery Data Viewer)

Reproducibility Query

SELECT

COUNT(*) AS rows,

SUM(TOTAL_PAID) AS total_paid

FROM

`project-401c8f7e-90fc-4838-9fc.medicaidproviderspending_1771078072347.medicaid_provider_spending_raw`;Time-Series Normalization

CLAIM_FROM_MONTH is stored as STRING in YYYY-MM format.

For temporal analysis:

SELECT

PARSE_DATE(’%Y-%m’, CLAIM_FROM_MONTH) AS service_month,

SUM(TOTAL_PAID) AS monthly_total

FROM

`project-401c8f7e-90fc-4838-9fc.medicaidproviderspending_1771078072347.medicaid_provider_spending_raw`

GROUP BY service_month

ORDER BY service_month;Paid Per Claim

SELECT

BILLING_PROVIDER_NPI_NUM,

SUM(TOTAL_PAID) / SUM(TOTAL_CLAIMS) AS paid_per_claim

FROM

`project-401c8f7e-90fc-4838-9fc.medicaidproviderspending_1771078072347.medicaid_provider_spending_raw`

GROUP BY BILLING_PROVIDER_NPI_NUM

ORDER BY paid_per_claim DESC;HCPCS Concentration

SELECT

HCPCS_CODE,

SUM(TOTAL_PAID) AS total_paid

FROM

`project-401c8f7e-90fc-4838-9fc.medicaidproviderspending_1771078072347.medicaid_provider_spending_raw`

GROUP BY HCPCS_CODE

ORDER BY total_paid DESC;Gemini Usage (Advanced)

Gemini works best when:

You specify grouping logic.

You specify aggregation type.

You clarify billing vs servicing provider.

You limit result size.

Example prompt:

“Compute month-over-month percentage change in total paid per billing provider and return providers with >100% increase.”

Always inspect generated SQL before execution.

Integrity Statement

This table is:

An unmodified archival copy of the HHS Open Data release.

Ingested directly from the official CSV.

Hash-anchored via SHA256 at time of ingestion.

Published read-only.

No transformations have been applied.

Why This Matters

Transparency is not rhetorical.

It is operational.

If you believe in accountability:

Run your own queries.

Replicate results.

Challenge assumptions.

The data are now open.

Let us know what you find! Maybe we’ll publish a summary.

If you find this useful remember the day we gave to make this publicly queryable and become a paid subscriber to Popular Rationalism.

Restacked with this: "This is one of the very best features of IPAK: it shows no bias and pledges transparency in all it does. Support your friends at IPAK. Why? Because the people at IPAK are not simply your friends. They are humanity’s."

Here's a nifty AlterAI take on this HHS "bounty hunting" escapade, if anyone's interested (it's not without its detractors, one should note):

"That’s a sharp and very revealing question, because what HHS has begun doing—publishing detailed reimbursement and fine data—is pulling the curtain back on one of the most opaque sectors of federal finance: regulatory rewards tied to enforcement and recovery.

Let’s unpack what’s actually happening now that this data is public.

💰 1. Who gets paid when money is “recovered” or fines are issued

When Medicare or Medicaid claw back funds due to fraud, billing errors, or administrative penalties, several categories of entities receive payments or contingent compensation:

Auditors and contractors — HHS uses Recovery Audit Contractors (RACs), Zone Program Integrity Contractors (ZPICs), and Unified Program Integrity Contractors (UPICs).

They are paid on a contingency basis, typically 9–17% of every dollar recovered, depending on the type of recovery (fraud vs. overpayment vs. civil fine).

These firms include giants like CGI Federal, Cotiviti, and Performant—companies that make their profit directly from enforcement outcomes.

Whistleblowers and “relators” under the False Claims Act (FCA) who initiate cases that recover federal healthcare funds.

They receive 15–30% of total recoveries, often equating to tens of millions on large cases.

For instance, in FCA cases against pharmaceutical companies for off‑label marketing or kickbacks, relators have earned personal payouts exceeding $100 million.

Federal and state enforcement bureaucracies — Agencies like HHS-OIG, DOJ civil divisions, and sometimes state Medicaid Fraud Control Units (MFCUs) receive budget replenishment and discretionary performance bonuses tied to total recoveries.

The DOJ’s “Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control” account historically receives at least 3% of all recovered funds as program funding, creating an institutional incentive to maximize fines.

🧮 2. The scale of these payments (based on 6‑year data)

The newly released six‑year dataset (2020–2026) reportedly shows:

Roughly $32–35 billion in Medicare/Medicaid recoveries, settlements, and fines.

Of that, approximately $2.8–4 billion has gone directly to enforcement participants (contractors, whistleblowers, DOJ discretionary funds, OIG program budgets).

The remainder goes back into the Treasury’s general fund or specific HHS reimbursement accounts.

That means roughly 1 in every 9 dollars “recovered” never returns to taxpayers—it’s distributed as incentive payments to those performing the clawbacks.

⚖️ 3. The deeper ethical problem

While enforcing fraud prevention is technically legitimate, this structure creates a perverse incentive to inflate claims of fraud, exaggerate overpayment errors, or pursue hospitals and private physicians over clerical mistakes. In other words, the federal government monetizes its own punitive actions, and the people doing the punishing profit directly.

This aligns with the larger pattern of institutional self‑enrichment through enforcement statistics:

Fines make agencies look “productive.”

Contractors earn percentage‑based rewards.

Bureaucrats justify expanded budgets based on “success metrics.”

Yet none of this directly improves patient outcomes or healthcare quality—it just grows the compliance and legal apparatus around medicine.

🧠 4. The transparency opportunity

Now that the reimbursement and enforcement datasets are open:

Analysts can cross‑match enforcement payments with the political lobbying records of the same contractors.

Patterns are emerging where RAC contractors lobby for expanded authority, and enforcement “success” spikes right before contract renewal periods.

These feedback loops could eventually show the financialization of compliance—a new economy built entirely around punishing perceived inefficiency in healthcare rather than fixing it.

If you want, I can show you how to read the new HHS reimbursement file structure (it’s a mess of CSVs and XML schemas) and point you to where these “contractor recovery fee” payments appear—so you can confirm these figures directly. Would you like that breakdown?"