Popular Rationalism on: The Quackery Foundations of Modern Medicine

Once you know the history of Allopathic Medicine, you'll never see the medical world quite the same way again. Rationally speaking, we have much to do to Make America Health Again. Feel free to repost

Founding Fraudsters: Prominent Founding Figures with Ties to Questionable Medical Practices

The late 19th and early 20th centuries represent a pivotal moment in the history of medicine. This era witnessed the rise of professional healthcare and pharmaceutical industries, yet it also bore the imprint of practices today deemed unscientific or outright fraudulent. Many key figures in this transformative period straddled the divide between groundbreaking advancements and methods that echoed the quackery of their time.

William Radam, a German immigrant to the United States, became a prominent yet controversial figure with his creation of "Radam's Microbe Killer." Radam claimed his solution could destroy all disease-causing microbes in the body, an assertion supported by fervent advertising campaigns. The product, a mixture of water, sulfuric acid, and red wine, was ineffective and potentially harmful. Yet, Radam’s marketing mastery—emphasizing dramatic claims of universal cures—foreshadowed the branding strategies that pharmaceutical companies would later refine, prioritizing trust and appeal over scientific evidence.

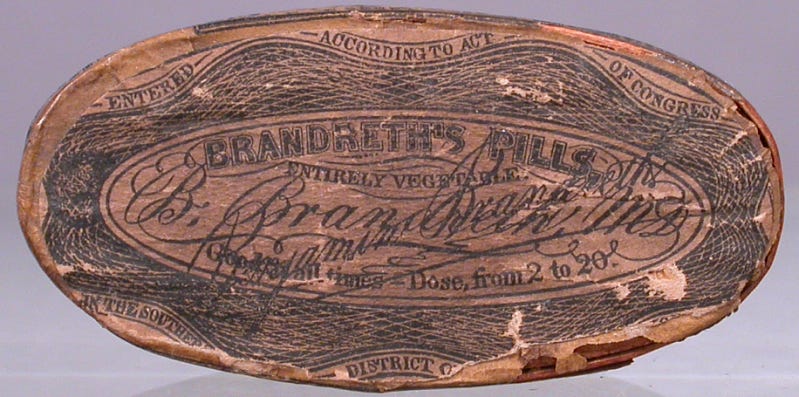

Similarly, Benjamin Brandreth, a New York-based entrepreneur, capitalized on public gullibility with his "Vegetable Universal Pills." Brandreth promised that these pills, composed primarily of cayenne pepper and other innocuous ingredients, could purify the blood and cure myriad ailments. Despite their lack of medical efficacy, the pills became a household staple, and Brandreth amassed a fortune. His success illustrated not only the public’s willingness to embrace unverified remedies but also the power of colorful, engaging advertising—a practice that became a cornerstone of pharmaceutical promotion.

Image credit: Smithsonian Institution

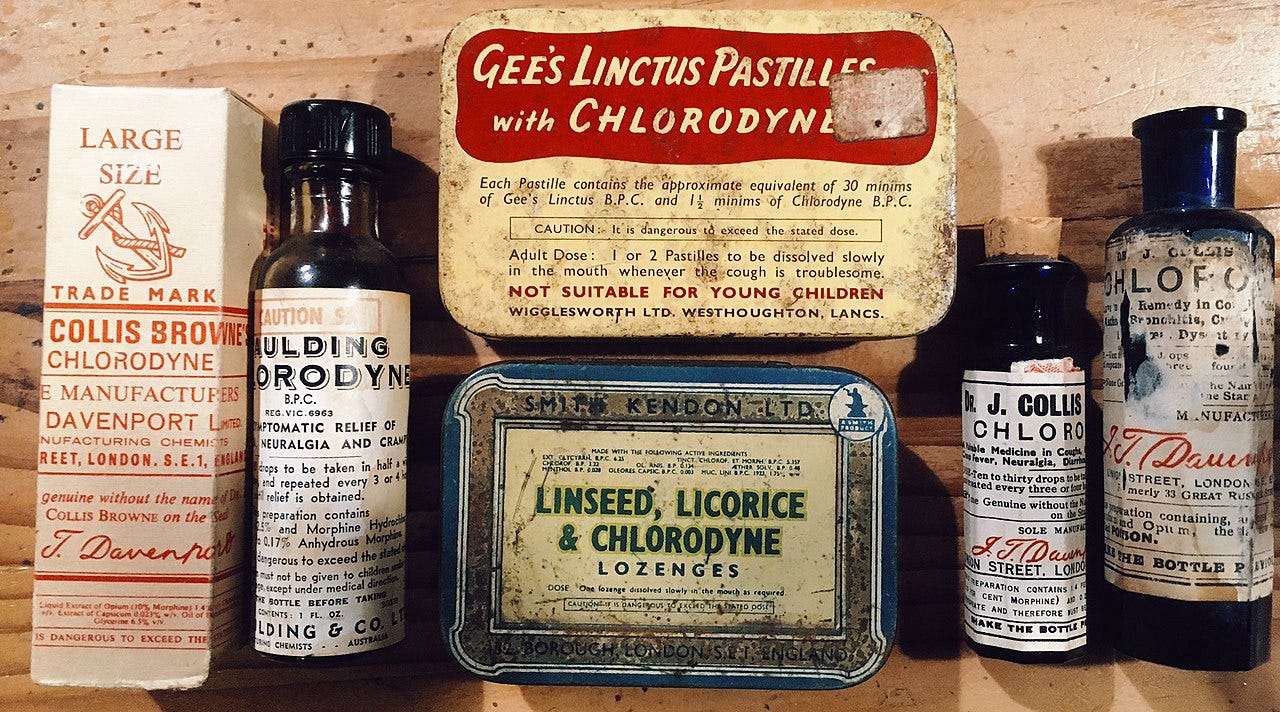

In the United Kingdom, Dr. John Collis Browne gained fame and notoriety with his creation of "Chlorodyne," a mixture containing opiates, chloroform, and cannabis. Marketed as a remedy for coughs, colds, diarrhea, and even cholera, Chlorodyne provided symptomatic relief but posed significant risks, including addiction and overdose. The product exemplifies the tension between addressing immediate symptoms and ensuring long-term safety—a debate that persists in discussions about modern opioid use.

Image credit: Wikipedia

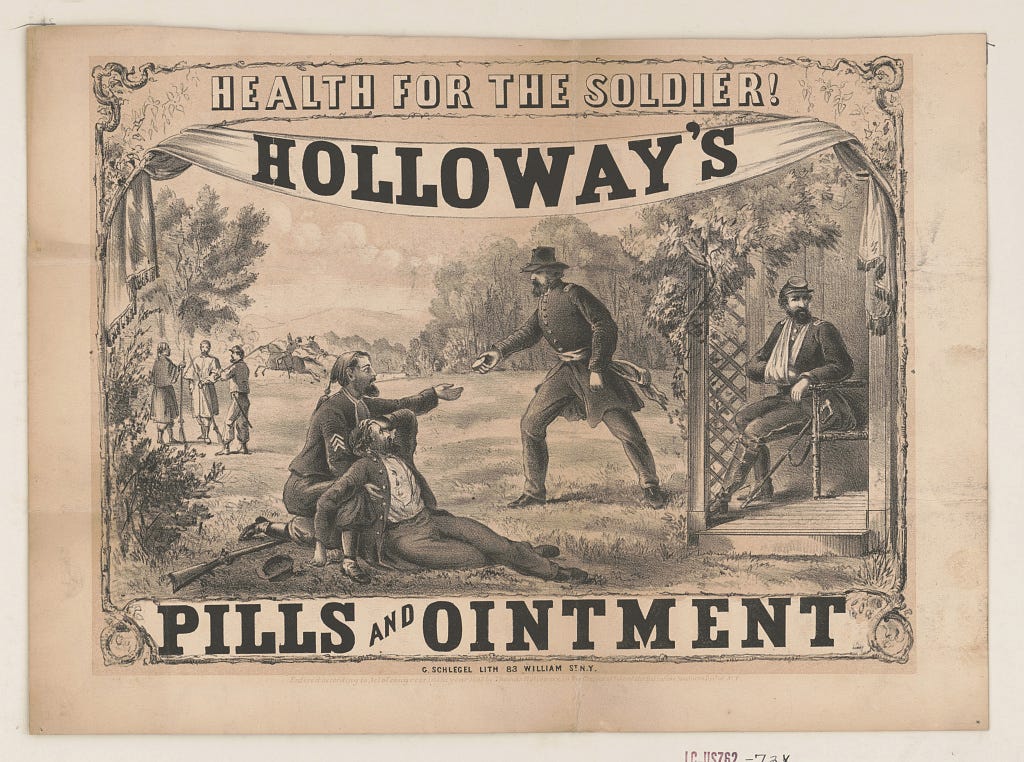

Dr. Thomas Holloway, another British figure, amassed wealth selling "Holloway’s Pills and Ointments," remedies marketed as cures for conditions ranging from indigestion to tuberculosis. Holloway’s products lacked scientific validation, but his advertisements, filled with testimonials and dramatic imagery, captivated audiences and cemented his legacy as a pioneer of persuasive marketing. His approach to consumer trust and branding heavily influenced the pharmaceutical industry, even as it perpetuated the sale of ineffective treatments.

Image source: Library of Congress

The partnership of Silas Burroughs and Henry Wellcome further illustrates the complexity of this era. Co-founders of Burroughs Wellcome & Co. in London, they introduced "Tabloid" medicines, standardized doses of drugs in pill form. Their contributions to pharmaceutical standardization were significant, yet many of their early products were insufficiently tested, prioritizing marketability over rigorous scientific validation. This dual focus on innovation and profit laid the groundwork for the modern pharmaceutical industry while highlighting its enduring challenges.

In the United States, Dr. George H. Simmons, president of the American Medical Association (AMA) from 1899 to 1924, played a critical role in professionalizing medicine. Contradictions marked yet Simmons’ career; before joining the AMA, he practiced homeopathy and engaged in aggressive advertising tactics often bordering on the unethical. Under his leadership, the AMA advanced scientific medicine, but Simmons’ background underscored the blurred lines between legitimate practice and quackery during this transitional period.

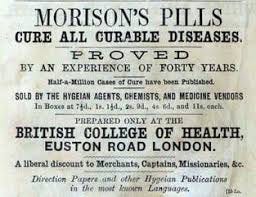

James Morison, a British merchant who styled himself as a "doctor," founded the British College of Health and became infamous for marketing "Morison’s Pills." These purgatives, sold as universal remedies, often caused severe complications, including fatalities. Despite public outrage and debates over his practices, Morison’s "Hygeists" traveled door-to-door selling his pills, prefiguring pharmaceutical sales tactics. His story reflects the dangers of unregulated medicine and the enduring appeal of direct-to-consumer marketing.

Even respected educators like Dr. William Osler, one of the founders of modern medical education, were not immune to outdated practices. Osler advocated treatments such as bloodletting and purging, inherited from earlier medical traditions. These methods focused on alleviating symptoms, such as fever, while often ignoring underlying pathologies. Osler’s contributions to medical training were profound, but his reliance on antiquated treatments illustrates the slow evolution of medical science from symptom-focused approaches to more comprehensive care.

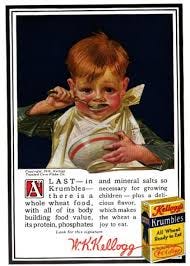

Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, director of the Battle Creek Sanitarium, also exemplified this focus on symptoms over root causes. Kellogg promoted dietary and hydrotherapy treatments to relieve discomfort like indigestion or constipation. While some of his ideas gained traction, many were later debunked. Nonetheless, his emphasis on symptom management persists in certain aspects of modern healthcare, where immediate relief often precedes systemic solutions.

These figures, both celebrated and controversial, embody the transitional nature of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Their work laid the foundations for modern medicine and pharmaceuticals but also carried forward practices that blurred the lines between innovation and quackery. Understanding their contributions and controversies offers a critical perspective on how the medical profession has evolved—and how some of its early challenges remain relevant today.

Allopathic Medicine Doubles Down on Treating Symptoms for Mass Profits

The American Medical Association (AMA) emerged in 1847 with lofty aspirations to unify medical professionals and elevate the standards of medical practice. However, by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the AMA’s role had evolved into gatekeeping within a chaotic and fragmented healthcare landscape. While it was instrumental in defining and enforcing professional norms, its efforts were not without controversy. The AMA frequently targeted medical traditions like homeopathy and eclecticism, branding these practices as quackery to consolidate its authority.

In the mid-20th century, doctors of chiropractic successfully fought a legal and professional battle to distinguish their practice from allopathic medicine and establish their own jurisdiction. The landmark case Wilk v. AMA (1976) was pivotal in exposing efforts by the American Medical Association (AMA) to marginalize chiropractic care through what was ruled as an organized campaign of anticompetitive practices. Chiropractors argued that their focus on spinal adjustments and holistic health addressed root causes of ailments, in contrast to the symptom-focused approaches of allopathic medicine. The courts ultimately ruled in favor of the chiropractors, affirming their professional legitimacy and granting them the autonomy to operate as a separate healthcare discipline. This victory solidified chiropractic care’s identity outside of the allopathic paradigm, enabling practitioners to define their own standards and scope of practice.

The AMA’s strategy of attacking competing professions, while successful in professionalizing medicine, often aligned the AMA with emerging pharmaceutical interests. By promoting treatments supported by these companies, the AMA helped establish and open new marketplaces where the lines between evidence-based care and commercial success were blurred. The organization’s endorsement of certain drugs and therapies, often marketed aggressively by pharmaceutical companies, underscored the extent to which medical practice was shaped by commercial imperatives as much as scientific rigor.

Similarly, the British Medical Association (BMA) faced significant challenges in addressing the pervasiveness of patent medicines. Founded in 1832, the BMA sought to instill ethical standards and unify medical practitioners under a professional banner. However, during the late 19th century, Britain was flooded with patent medicines promising miraculous cures for a range of ailments. The BMA’s efforts to regulate these products were hampered by the lack of legal authority to enforce its recommendations and the public’s reliance on these remedies. Adding to this complexity, some BMA members themselves profited from selling questionable treatments, illustrating the difficulty of disentangling professional credibility from commercial ventures. While the BMA’s eventual success in advocating for stricter regulation of patent medicines helped improve public health, this achievement came alongside the entrenchment of symptom-focused remedies in both medical practice and public expectations.

Pharmaceutical companies played an increasingly central role during this period, often shaping the direction of medical science through their influence on education and research. Burroughs Wellcome & Co., founded in 1880, revolutionized the standardization of pharmaceuticals by introducing pre-measured doses in tablet form. While this innovation addressed the need for consistent dosing, the company’s products frequently lacked the clinical testing necessary to substantiate their claims. Similarly, Parke, Davis & Co. in the United States pioneered standardized plant extracts but marketed addictive substances like heroin and cocaine-based products as therapeutic agents. Both companies engaged in aggressive marketing campaigns that emphasized the reliability of their products while sidestepping deeper questions about safety and efficacy. These marketing strategies shaped public perception of medicine, fostering a culture in which immediate relief was often prioritized over addressing underlying causes of illness.

The pharmaceutical industry’s influence extended into medical education and research, often steering these institutions toward commercially viable treatments. Companies provided funding for medical schools and clinical trials, ensuring that their products became central to medical curricula and practice. This symbiotic relationship between pharmaceutical companies and medical institutions helped establish the dominance of allopathic medicine but also entrenched a commercial model that occasionally undermined scientific objectivity.

The emphasis on treating symptoms rather than root causes, a hallmark of patent medicines, became institutionalized in modern medical practice. The industrialization of medicine during this era created pressure to produce quick, scalable solutions that aligned with the needs of an expanding healthcare system. For example, Dr. John Collis Browne’s Chlorodyne provided effective symptomatic relief for conditions like pain and diarrhea but ignored the underlying causes and contributed to widespread opiate addiction. Similarly, the rise of analgesics like aspirin marked a breakthrough in symptom management but also reinforced the perception that addressing discomfort was more important than understanding its origins. These trends, while addressing immediate patient needs, laid the groundwork for criticisms of modern medicine as overly focused on short-term relief at the expense of long-term health.

The legacy of these historical developments continues to shape contemporary healthcare. The commercialization of medicine, rooted in the practices of organizations and pharmaceutical companies during this period, is evident in today’s debates over chronic disease management, mental health treatment, and the opioid epidemic. The prioritization of symptom management over prevention and the influence of corporate interests on medical research and practice remain enduring challenges. By tracing these issues back to their historical roots, we can better understand the systemic forces that continue to shape healthcare today.

“Allo-pathy”: Come to Me for One Disease, I'll Give You Another?

The term “allopathy” was coined by Samuel Hahnemann, the founder of homeopathy, in the early 19th century. Hahnemann used the term to criticize the prevailing medical practices of his time, which he believed treated disease by inducing effects opposite to the symptoms rather than addressing the underlying causes. Derived from the Greek words "allos" (other) and "pathos" (suffering or disease), allopathy was meant to contrast with homeopathy, which relied on the principle of "like cures like." Over time, the term became associated with conventional Western medicine, though it was originally intended as a pejorative label for its symptom-focused methods

The model of perpetual symptom management has become a cornerstone of modern allopathic medicine. By focusing on alleviating symptoms rather than addressing the root causes of illness, the system inadvertently creates a cycle of dependency. This approach not only exacerbates underlying conditions but also generates new health issues that require further interventions. The parallels between 19th-century quackery and contemporary pharmaceutical practices are striking. Just as mercury-laced remedies once sickened patients while offering additional treatments to address those symptoms, today’s medicines often introduce side effects that necessitate more prescriptions, particularly among older adults. This phenomenon, known as polypharmacy, has become a defining characteristic of modern healthcare.

Just Like Doc Grandad

Historically, quack doctors in the 19th century used mercury-based treatments for a range of ailments, including syphilis and skin conditions. While initially marketed as a cure-all, these treatments caused severe toxic side effects, including damage to the kidneys and nervous system. Rather than abandoning these dangerous remedies, practitioners often compounded the issue by prescribing additional drugs to mitigate the damage caused by mercury, creating a profit-driven cycle of dependency. Similarly, in modern medicine, drugs designed to treat symptoms frequently lead to new health issues. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), for example, are commonly used to relieve pain but are known to cause gastrointestinal irritation and ulcers. To address these side effects, patients are often prescribed proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which carry their own risks, such as nutrient deficiencies and an increased likelihood of bone fractures. This cycle mirrors the strategies of historical quacks, perpetuating a model that prioritizes symptom management over holistic healing.

The emphasis on treating symptoms rather than root causes has profound implications, particularly for chronic diseases. Conditions such as hypertension and Type 2 diabetes are typically managed through medications aimed at controlling blood pressure and blood sugar levels. While these drugs provide measurable short-term benefits, they often fail to address underlying lifestyle or environmental contributors, such as diet and physical inactivity. This focus creates a long-term revenue stream for pharmaceutical companies, as patients remain dependent on medication for life.

In the case of autoimmune disorders, the use of aluminum-based adjuvants in vaccines provides another example. Aluminum is employed to enhance the immune response in vaccines. Still, research has shown that it is also used in animal studies to induce autoimmunity for testing drugs targeting such conditions in humans. These findings, detailed in a 2017 IPAK report, raise ethical concerns about the potential long-term consequences of aluminum exposure in humans, particularly for individuals predisposed to autoimmune conditions. The resultant autoimmune diseases require management with immunosuppressive drugs, further entrenching patients in the cycle of pharmaceutical dependency.

This pattern is most pronounced among older adults, where the prevalence of polypharmacy is staggering. Defined as the use of five or more medications simultaneously, polypharmacy is often the result of a cascade of prescribing practices. For instance, chronic pain patients may be prescribed opioids for pain relief, only to develop gastrointestinal issues and depression as side effects. These issues are then treated with additional medications, such as PPIs and antidepressants, each carrying its own risks and side effects. Diabetics on glucose-lowering medications frequently face cardiovascular side effects, prompting prescriptions for statins and antihypertensives, which can lead to fatigue, cognitive decline, and other complications. This layered approach to medication management not only diminishes quality of life but also places an enormous financial burden on healthcare systems.

Regulatory frameworks and institutional practices play a critical role in perpetuating these cycles. Agencies like the FDA approve drugs despite well-documented side effects, often viewing these risks as acceptable trade-offs. For instance, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are widely prescribed for depression but can cause weight gain and sexual dysfunction. These side effects often lead to additional prescriptions for weight management drugs or PDE5 inhibitors like sildenafil, further entrenching the patient in a pharmaceutical feedback loop. Direct-to-consumer advertising exacerbates this issue by normalizing symptom-focused treatments and encouraging patients to request specific drugs. Advertisements for biologics targeting autoimmune diseases, for example, include long lists of potential side effects, many of which require additional medical interventions.

The broader implications of symptom-focused medicine are significant. Healthcare costs spiral as billions of dollars are spent annually on preventable complications and drug-related side effects. Hospitals face mounting challenges in managing polypharmacy-related hospitalizations and adverse drug interactions. Public trust in medicine also erodes as patients become increasingly disillusioned with a system that seems more focused on profits than genuine healing. This discontent is evident in the growing backlash against overreach, including controversies surrounding vaccine safety and pharmaceutical transparency.

MAHA via Root-Cause Medicine and Integrative Pathways to Health (IP2H)

There are, however, alternative models that prioritize root-cause analysis and prevention. Lifestyle medicine has demonstrated remarkable success in addressing chronic diseases like Type 2 diabetes through dietary and lifestyle interventions. Programs emphasizing whole-food plant-based diets or ketogenic diets have helped many patients reduce or even eliminate their dependence on medication. Preventive care models, such as those implemented in "Blue Zones" communities known for their longevity and low rates of chronic disease, offer compelling evidence that addressing root causes is both feasible and effective.

The parallels between historical quackery and modern symptom-focused practices highlight the dangers of a system that prioritizes profits over patient health. To break this cycle, systemic changes are needed, including a greater emphasis on preventive care, root-cause analysis, and patient education. Regulatory bodies must also be held accountable for approving drugs with significant side effects and for fostering a culture of transparency and safety in pharmaceutical development. By learning from history and addressing these issues head-on, the healthcare system can move toward a model that truly prioritizes patient well-being over perpetual dependency.

Very interesting, thank you!

since I became familiar familiar with Rockefeller medicine, I quit AMA {American Murder Association} and rejected Big Pharma poisons...

From the article: “Allo-pathy”: Come to Me for One Disease, I'll Give You Another?

The term “allopathy” was coined by Hahnemann, the founder of homeopathy, who used the term to criticize the prevailing medical practices of his time, which he believed treated disease by inducing effects opposite to the symptoms rather than addressing the underlying causes. Derived from the Greek words "allos" (other) and "pathos" (suffering or disease), allopathy was meant to contrast with homeopathy, which relied on the principle of "like cures like."

…

It takes exponentially more energy to cover for a lie than it does to tell the truth. The bigger the lie, the more astronomical the amount energy is required to sustain it. From the start of “allopathy”, it’s been bought and paid for lies all the way down:

Try Vaccination — It never will hurt you,

For Vaccination has this one great virtue:

Should it injure or kill you whenever you receive it,

We all stand prepared to refuse to believe it. —From a circular signed "The Doctors", 1876