FDA Continues Crackdown on Accuracy in DTC Marketing

The billions spent to mislead Americans into seeking health in a pill are not being scrutinized.

The FDA has significantly escalated its scrutiny of direct-to-consumer (DTC) drug marketing, culminating in a wave of enforcement actions in 2025 that have surpassed the cumulative number of promotional compliance letters issued across the previous decade. This unprecedented surge, led by the Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP), reflects a decisive shift in regulatory posture toward greater accountability in how pharmaceutical manufacturers communicate efficacy, risk, and benefit to the public. Early signs in 2026 suggest the agency is not merely sending a signal, but implementing a durable shift in enforcement intensity.

FDA’s Commissioner of Food and Drugs, Marty Makary, posted to X:

“New reporting out: @US_FDA’s crackdown on direct-to-consumer drug ads is having a big impact. And we’re just getting started.”

The scope of this crackdown centers on promotional materials for FDA-approved prescription drugs, excluding compounded drugs and investigational products. It includes untitled letters, which note violations without immediate legal consequences, and more serious warning letters that often precede further legal or regulatory action. The OPDP’s jurisdiction spans any promotional material targeting consumers or healthcare providers, including television ads, digital and print campaigns, and social media. The crackdown reflects heightened scrutiny especially for products with boxed warnings, REMS (Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies), or a history of prior violations.

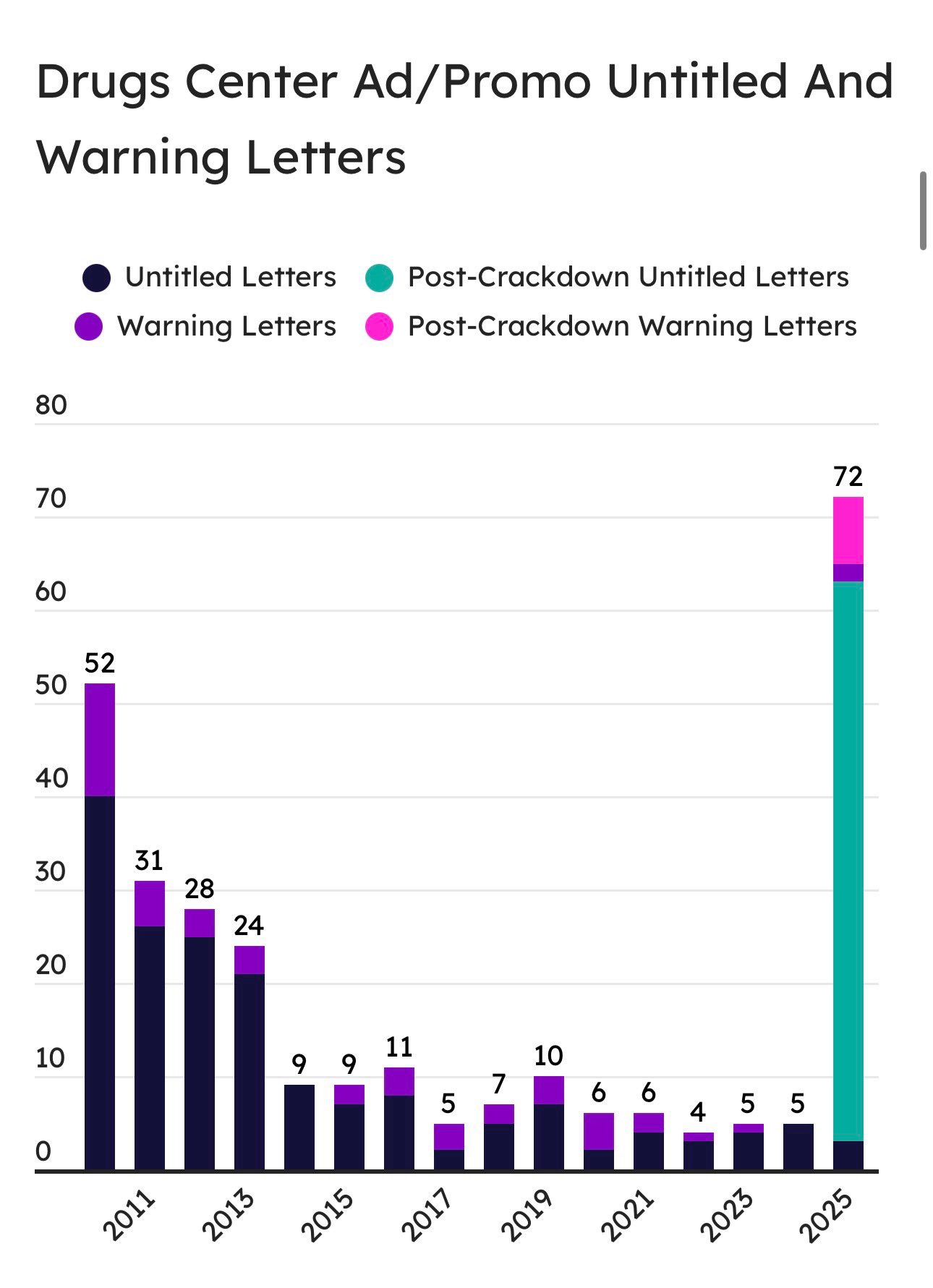

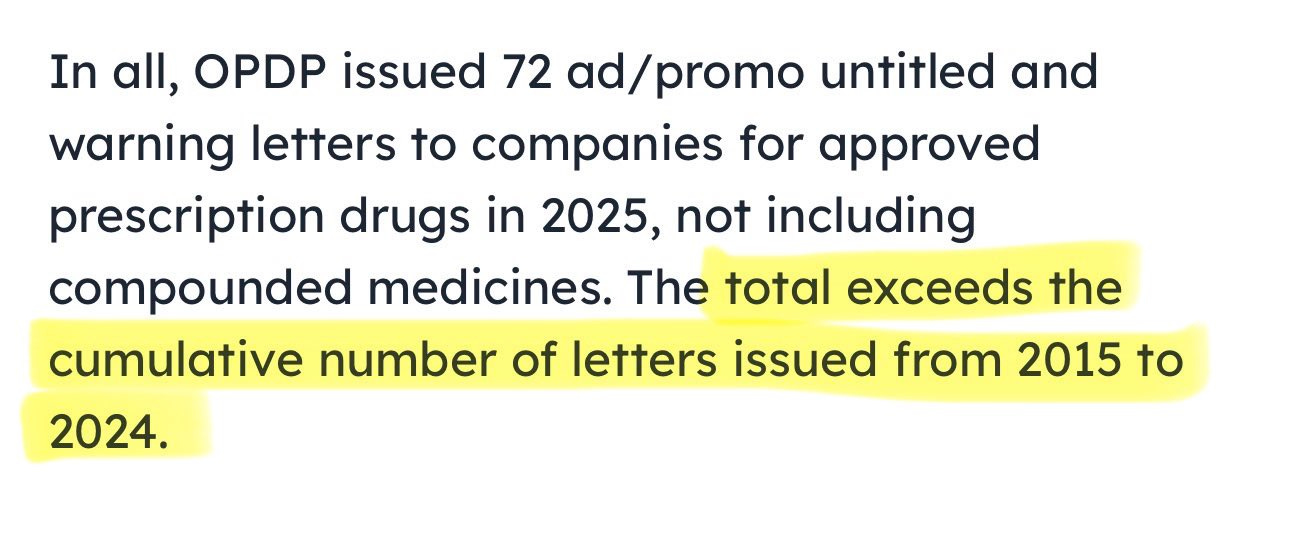

From 2015 to 2024, the OPDP issued between 4 and 11 promotional compliance letters annually. In 2025 alone, that number spiked to 72, exceeding the total for the entire prior decade. A plurality of those 72 were untitled letters triggered by post-marketing surveillance of high-profile DTC ads, particularly on television and social media. Several warning letters were also issued, particularly in Q3 and Q4, where sponsors failed to disclose serious risks, overstated efficacy, or made unsupported superiority claims. As of January 2026, multiple untitled letters have already been posted, signaling that this is not an anomaly but an emerging enforcement regime.

A year-by-year count underscores the escalation. Between 2011 and 2024, OPDP issued an average of 8.2 letters per year. In 2025, 72 letters were posted. This tenfold increase is not merely quantitative; it reflects changes in letter content, targeted media, and risk classification. Of those 72 letters, 59 were untitled and 13 were formal warning letters. Notably, 31 involved DTC television advertising, and over 50% implicated products carrying boxed warnings. January 2026 has already seen additional letters issued to sponsors of Brukinsa, ANKTIVA, and NEFFY, targeting specific TV and website materials.

(Source: US FDA)

The underlying regulatory framework stems from the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (§502(n), §505) and 21 CFR 202.1. These establish a baseline of fair balance, prohibiting any promotion that misbrands a drug through the omission of material facts or exaggeration of benefits. Enforcement hinges on whether claims are supported by substantial evidence, typically derived from adequate and well-controlled trials, and whether risks are disclosed with equal prominence to benefits. The OPDP also evaluates whether the “net impression” left by an ad is truthful and not misleading, irrespective of disclaimers.

Data for this report were extracted directly from FDA’s OPDP enforcement indices, cross-referenced against the FDA’s warning letter archive. All posted letters from 2011 through January 2026 were included. Duplicates, closeouts, and re-postings were excluded. Yearly totals were assigned based on the date of letter issuance, not posting. Letter content was parsed for claim type, promotional medium, therapeutic area, and risk tier. Violations were then coded according to a schema aligned with 21 CFR 202.1 and OPDP guidance. All data and code used to generate figures are made publicly available.

Three representative cases illustrate this shift. One letter targeted a TV ad that presented a treatment for a chronic inflammatory condition with dramatic visual transformations while relegating its boxed warning to rapidly scrolling fine print and a muffled voiceover. Another focused on a disease-awareness website that subtly redirected readers to a branded page with comparative claims not supported by head-to-head trials. A third cited a social media campaign that claimed a breakthrough in preventing recurrent episodes without disclosing that the underlying trial failed to meet its primary endpoint.

These violations highlight recurring breakdowns in how efficacy is communicated. Among the most common: reporting relative risk reduction without absolute risk; conflating surrogate and clinical endpoints; bundling multiple endpoints into a composite that masks net harm; relying on subgroup analyses without proper adjustment; and overinterpreting real-world evidence or post-hoc observational results as equivalent to trial-grade evidence. Sponsors also continue to imply prevention or cure when trials only support symptom reduction.

Equally troubling are the failures in risk communication. Many DTC materials continue to downplay boxed warnings, bury contraindications, or present risks in ways that are visually or audibly subordinate to benefits. Web pages often hyperlink critical safety data rather than presenting it inline. In some cases, promotional content appears structured to satisfy formal disclosure rules while clearly attempting to minimize their persuasive impact on the viewer.

Industry appears to be taking notice. Anecdotal reports and interviews with regulatory affairs professionals suggest that sponsors are re-evaluating their ad portfolios and proactively modifying claims. This includes pulling back from quantitative benefit language, reevaluating placement of risk content within promotional pieces, and shifting toward disease-awareness framing—though not always successfully staying within the FDA’s permissive bounds.

The downstream impacts of misleading promotion are not cosmetic. Overstated claims and under-disclosed risks affect prescribing behavior, drive inappropriate patient demand, distort perceptions of risk-benefit ratios, and may crowd out better therapeutic choices. They also erode public trust in science-based medicine and place clinicians in the difficult position of managing unrealistic patient expectations shaped by misleading media.

To address this, the FDA could pursue several reforms. These include mandatory submission of all DTC ads for pre-review for high-risk products; standardized ad disclosures using “Risk Boxes” and “Outcomes Boxes” similar to nutrition labeling; required inclusion of absolute risk data for all efficacy claims; machine-readable submission of promotional materials to enable automated audit; escalating penalties for repeat offenders; and public scoring of sponsors based on compliance quality.

Metrics must evolve beyond raw letter counts. More meaningful indicators include median time to ad correction following OPDP action, repeat violation rates by sponsor or product, proportion of letters with major versus minor findings, frequency of withdrawn versus corrected ads, and measurable alignment of ad language with FDA-approved labeling and trial protocols. We propose the FDA publish a quarterly OPDP Compliance Score that reflects these dimensions.

Anticipated objections include claims of regulatory overreach or concerns that strict enforcement will chill innovation. Some sponsors may argue that post-market evidence or real-world data justifies more aggressive claims. Others may hide behind formal disclosures while intentionally crafting misleading net impressions. These defenses must be met with clarity: speech about drug claims is not protected if it misleads. Innovation is not chilled by integrity, and transparency is not optional when lives are at stake.

The promotional ecosystem is complex. Many violations originate not with the sponsor directly, but with marketing agencies operating with performance incentives, medical ghostwriters crafting untraceable claims, or PR intermediaries blurring lines between education and advertising. Greater transparency is needed on these third-party roles, with disclosure of all promotional subcontractors, their compensation, and their ad development responsibilities. Failure to disclose these relationships should trigger enhanced scrutiny.

The FDA’s 2025 crackdown and its early 2026 continuation mark an inflection point. With both regulatory muscle and public momentum, the agency has an opportunity to permanently raise the floor on promotional accuracy. Done right, this will protect patients, support prescribers, and reward companies that invest in evidence-driven communication. The challenge now is to institutionalize the gains, build rigorous metrics, and ensure this accountability becomes the new normal.

OPDP enforcement is also complicated by the rise of AI-generated ad content, where large language models could inadvertently generate claims beyond label or misinterpret endpoints. As drug companies experiment with generative content, FDA must develop methods to audit AI-originated promotional language.

Finally, any enduring reform must illuminate the opaque marketing ecosystems. Ghostwriting, performance-based ad agencies, and disease awareness front groups muddy the attribution chain. FDA should require sponsors to disclose all entities involved in ad development and placement, including their contractual terms. Failure to disclose should be treated as a compliance violation.

The FDA’s 2025 crackdown is not a blip. It is a necessary reckoning. The regulatory regime that emerges must reward sponsors who respect the evidentiary basis of approval and penalize those who exploit the gray areas of promotional language. Only by institutionalizing this accountability—through metrics, transparency, and statutory modernization—can the agency ensure that promotional accuracy is not the exception, but the rule.

RESOURCES

FDA Enforcement Documents

FDA OPDP Untitled Letters Index (Live List)

https://www.fda.gov/drugs/warning-letters-and-notice-violation-letters-pharmaceutical-companies/untitled-lettersFDA OPDP Warning Letters Index

https://www.fda.gov/drugs/warning-letters-and-notice-violation-letters-pharmaceutical-companies/warning-lettersFDA Press Release – Crackdown Announcement (Sept 9, 2025)

https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-launches-crackdown-deceptive-drug-advertisingLetter to Industry (Sept 9, 2025) – Official directive from FDA CDER

https://www.fda.gov/media/188616/download

Notable OPDP Letters (Examples Cited)

ANKTIVA – Untitled Letter (January 7, 2026)

https://www.fda.gov/media/190567/downloadANKTIVA – Untitled Letter (September 9, 2025)

https://www.fda.gov/media/188898/downloadNEFFY – Untitled Letter (September 9, 2025)

https://www.fda.gov/media/188705/downloadBRUKINSA – Mentioned in Jan 2026 Letters (Confirmed by Fierce Pharma)

https://www.fiercepharma.com/marketing/fda-chides-beone-immunitybio-promo-materials-first-untitled-letters-2026

FDA Regulatory Framework

21 CFR 202.1 – Prescription Drug Advertising Regulations

https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-D/part-202/section-202.1FDCA Section 502 – Misbranding Provisions

https://www.fda.gov/media/72253/download (see §502(n))FDCA Section 505 – New Drug Application (NDA) Provisions

https://www.fda.gov/media/72253/download (see §505)

Contextual and Secondary Reporting

FDA’s September 2025 Wave of Letters – Summary Coverage

https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/fda-blitzes-12-drugmakers-promotional-violations-marketing-materialsProPharma Summary of OPDP Trends

https://www.propharmagroup.com/insights/opdp-enforcement-trends-fda-letter-blitz/Health Canada’s Advertising Regulatory Framework (Comparative Reference)

https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/regulatory-requirements-advertising.htmlUK MHRA Blue Guide – Promotion of Medicines

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/blue-guide-advertising-and-promoting-medicines

We need to go back to the days when pharmaceutical ads were banned!

Alongside New Zealand, we are the tiny minority of countries that allow it. Just the 2 of us!

"present risks in ways that are visually or audibly subordinate to benefits." Oh Pharma is pretty good at this. And it the medical community is affected as well.

"Ghostwriting, performance-based ad agencies, and disease awareness front groups muddy the attribution chain." THIS. Disease awareness groups can act as drug company promoters and sometimes (though not always) not realize it. This is why I do not give money to many disease advocacy groups anymore.