COVID-19 Vaccine Limited Immunity Durability Was Knowable from the Start: No Long-Lived Plasma Cells

Completely knowable from the first small trial.

The rapid decline of immunity after COVID-19 vaccination has left many wondering why these vaccines, despite their initial success, have not provided lasting protection. But what if the problem wasn’t a surprise at all? What if, based on long-established methods used to study basic immunology, we could have anticipated this outcome? Recent research has confirmed that one critical piece of the puzzle—long-lived plasma cells (LLPCs)—is missing from the immune response generated by mRNA vaccines, raising questions about whether the limitations of these vaccines were knowable from the start.

Introduction

The durability of immune protection is directly linked to the presence of long-lived plasma cells (LLPCs) in the bone marrow. These specialized cells produce antibodies over extended periods, often for years or decades, following infection or vaccination. Without LLPCs, the immune system cannot maintain long-term antibody levels, leading to a gradual loss of protection against the targeted pathogen.

The failure of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines to establish LLPCs was predictable. Immunologists have long known that LLPCs are essential for lasting immunity, and the absence of these cells means that vaccine-induced protection is inherently short-lived. Given this understanding, it’s worth examining why the potential durability issues with mRNA vaccines were not more thoroughly considered during their development and rollout.

Aims of the Study

A recent study led by F. Eun-Hyung Lee aimed to investigate why antibody levels decline so rapidly after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination. Specifically, the study sought to determine whether these vaccines could generate LLPCs, the cells responsible for maintaining antibody levels long after the initial immune response has faded. The question at the heart of the study was simple but profound: Did the mRNA vaccine fail to establish LLPCs as some immunologists had predicted?

What They Did

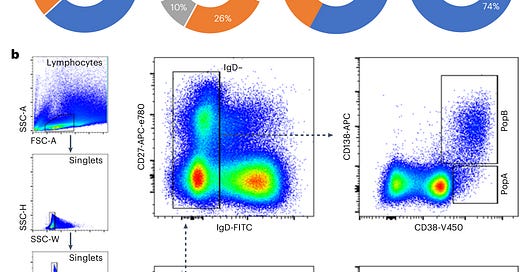

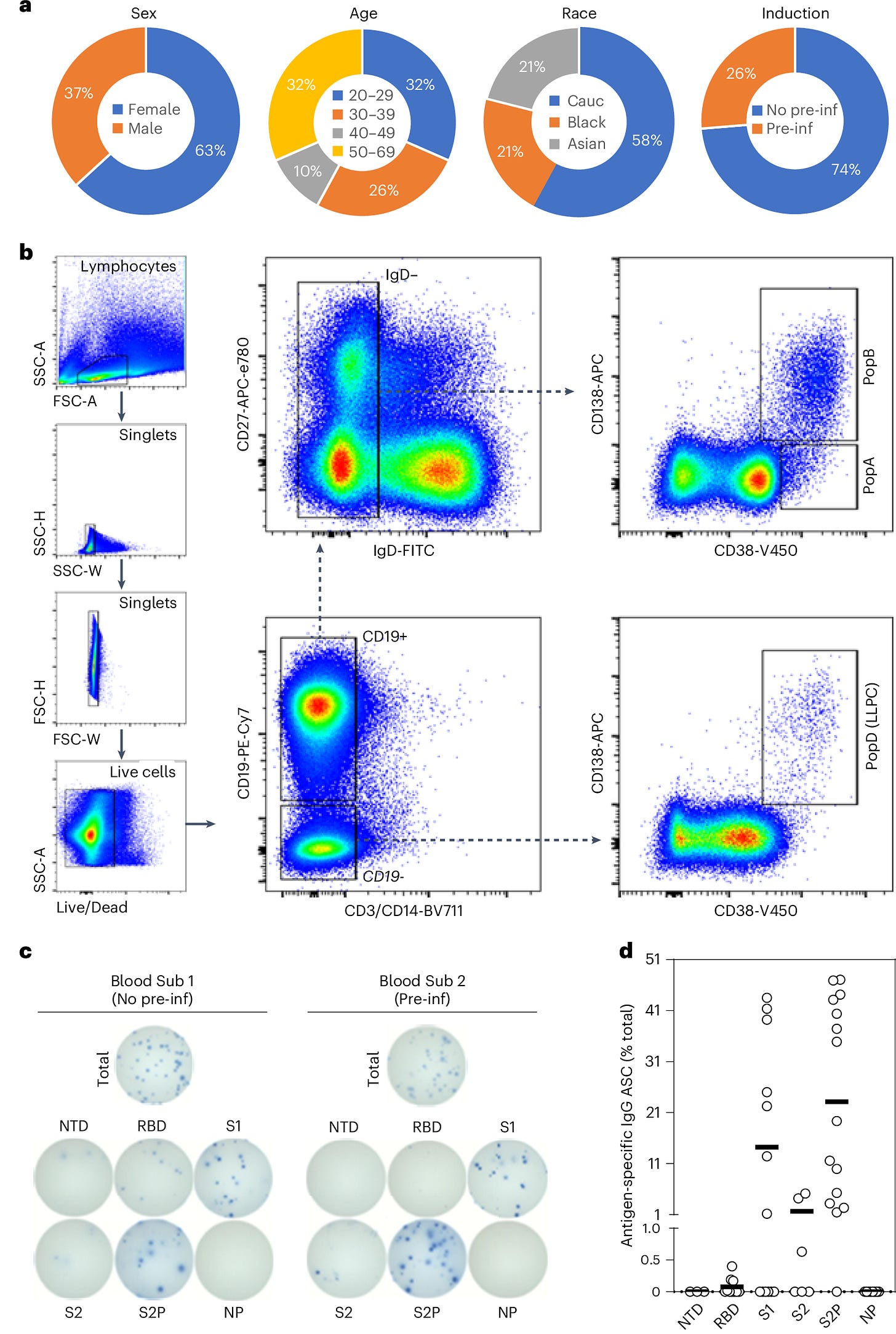

To address this question, researchers collected bone marrow samples from individuals who had received mRNA vaccines and compared them to samples from people vaccinated against other diseases, such as flu and tetanus. Using single-cell transcriptomics, they analyzed plasma cell populations, focusing on whether LLPCs specific to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein were present in the bone marrow.

By comparing these results to known LLPC populations for flu and tetanus vaccines, the researchers could determine whether the absence of LLPCs was specific to the COVID-19 vaccine platform or a broader immunological issue.

What They Found

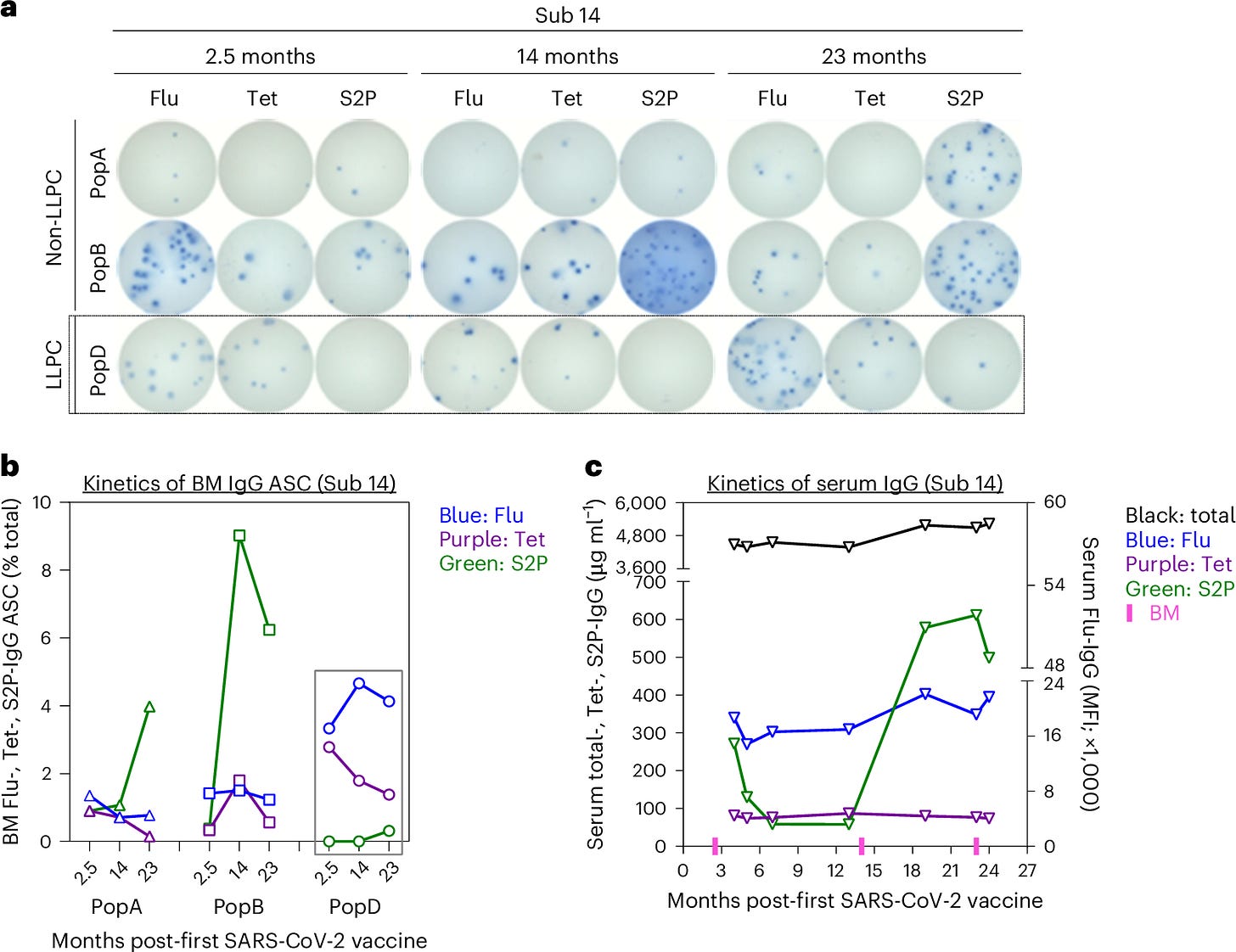

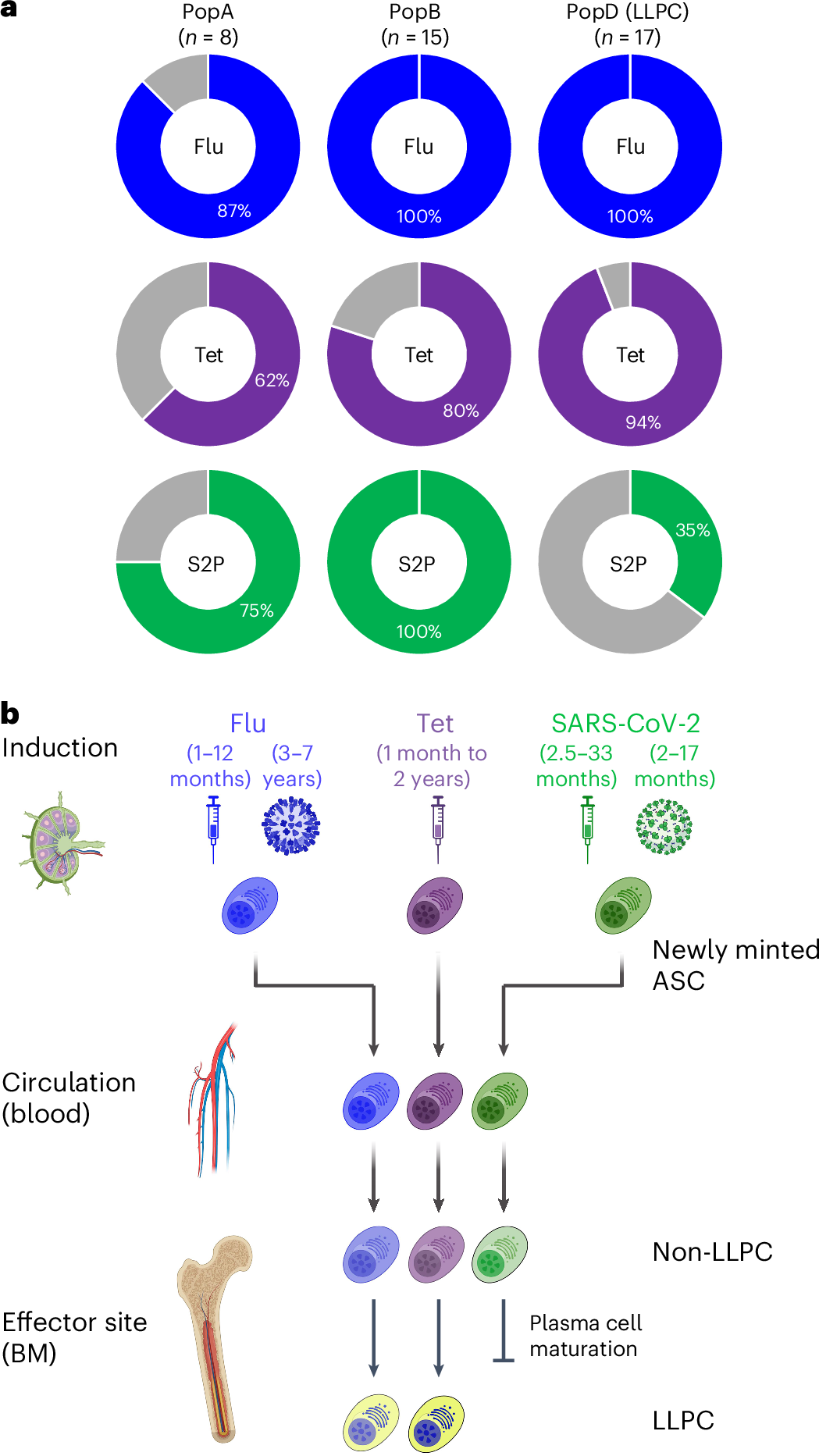

The results were clear: No SARS-CoV-2-specific LLPCs were found in the bone marrow of individuals vaccinated with mRNA vaccines, even in those who had also been infected with the virus. This was visualized in the study’s Figure 1, which showed that SARS-CoV-2-specific LLPCs were nearly undetectable in vaccinated individuals. In contrast, LLPCs for tetanus and flu vaccines were readily found, supporting the idea that the mRNA platform uniquely failed to induce these long-lived immune cells.

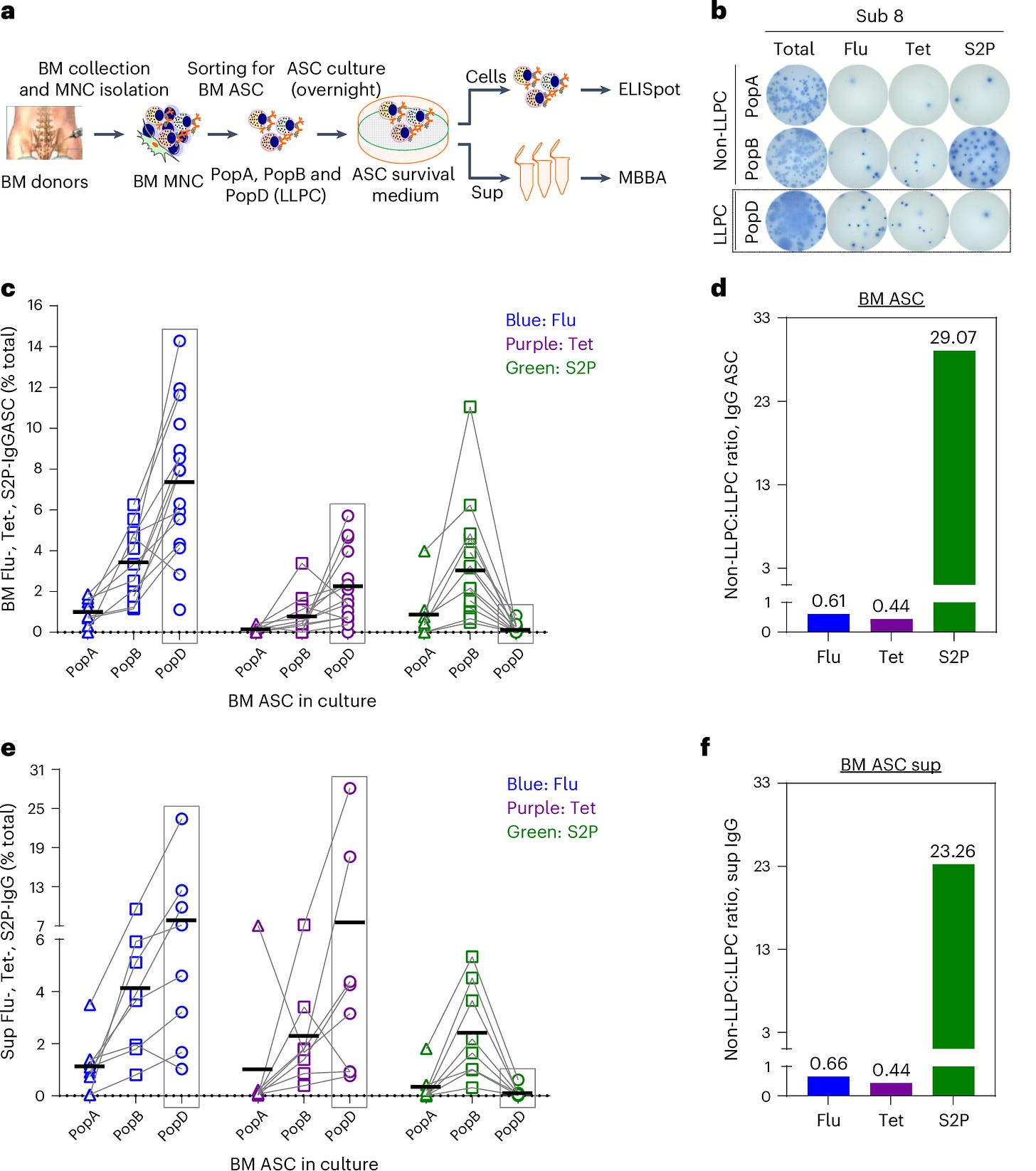

Figure 2 further emphasized the distinction between short-lived and long-lived plasma cells by tracking IgG, IgA, and IgM responses over time. It highlighted that the majority of the plasma cells responding to the mRNA vaccine were short-lived, with rapid declines in antibody levels after just a few months. LLPCs, which are responsible for long-term immunity, were conspicuously absent from the SARS-CoV-2-specific responses.

The study also found that IgA-secreting plasma cells, which are crucial for mucosal immunity in the respiratory system, were similarly absent. This adds another layer of complexity, as mucosal immunity is vital for protecting against respiratory viruses like SARS-CoV-2. Without these long-lived plasma cells, both systemic and mucosal immunity wane over time, explaining the rapid decline in vaccine-induced protection.

Figure 3 showcased the differences in plasma cell survival between traditional vaccines and the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. While flu and tetanus vaccines led to long-lasting LLPC populations, the spike-specific plasma cells induced by mRNA vaccines failed to survive long-term, significantly reducing IgG and IgA isotypes over time.

Significance of the Study

The absence of LLPCs explains the waning immunity observed after COVID-19 vaccination. Antibody levels decline rapidly because the body is not producing the long-lived cells necessary to maintain them over the long term. Figure 4 illustrated the sharp decline in circulating antibodies following mRNA vaccination compared to the more gradual decline observed after flu and tetanus vaccinations, underscoring the importance of LLPCs for durable immunity.

Perhaps most striking is the fact that this outcome was predictable. Immunologists have long understood the role of LLPCs in generating lasting immunity, and flu and tetanus vaccines are known to establish these cells effectively. The failure of mRNA vaccines to produce LLPCs should have raised red flags early in the development process.

The findings from this study suggest that the limitations of mRNA vaccines could have been foreseen. The translational research around the mRNA platform missed a critical component of durable immunity by focusing on short-term antibody responses rather than long-term immune memory. This has significant implications for the future of vaccine translational research.

This Was All Knowable - Boosters Were Preventable

Given what was already known about LLPCs before the COVID-19 pandemic, it is surprising that more attention wasn’t paid to their potential absence in mRNA vaccine-induced immunity. LLPCs are not a novel discovery—immunologists have long recognized their importance in providing sustained protection after infection. The fact that mRNA vaccines, designed to induce a potent but short-lived antibody response, would fail to generate these cells could have been anticipated.

The rush to develop vaccines during the pandemic placed a premium on speed, but it’s worth asking whether the scientific community should have been more forthright about the type of evidence needed to warrant scale-up to mass vaccination. This study would not have taken much longer. After the initial clinical trials, Fauci and friends told the world that we would have to wait until the vaccines were used on hundreds of thousands of people to determine if they induced durable immunity. That was false.

Some have argued that perhaps mucosal vaccines have been given more consideration, which might have stimulated IgA-secreting plasma cells and provided better protection against respiratory transmission.

It entirely depends on epitope selection - which should be done in a way that will avoid #PathogenicPriming and #ADE.

The primary point is that vaccines that fail to establish LLPCs, regardless of their short-term efficacy, will leave populations vulnerable to future outbreaks and reinfections.

Implications

The failure of mRNA vaccines to generate long-lived plasma cells was not a surprise—it was a foreseeable outcome based on established immunological principles. LLPCs are the foundation of durable immune protection, and without them, the body cannot maintain sufficient antibody levels to prevent infection over the long term.

As Figure 5 pointed out, long-lived plasma cells are the key to sustaining antibody titers over time, and their absence in the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine response means that protection will continue to wane without frequent boosters. And that was likely the point.

As we look toward the future, the lessons from this experience are clear: any vaccine development must prioritize long-term immunity and by hypervigilance against short- and long-term risks. Whether through alternative platforms, different antigens, or new routes of administration, the next generation of vaccines must focus on establishing LLPCs and ensuring that protection lasts well beyond the initial immune response.

Nguyen, D.C., Hentenaar, I.T., Morrison-Porter, A. et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific plasma cells are not durably established in the bone marrow long-lived compartment after mRNA vaccination. Nat Med (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03278-y

This is in direct contrast to natural immunity following infection that does produce LLPC. (I read a study on it in early 2021 that talked extensively about the results meaning natural immunity lasted at least 5 years)

Do you think people who took the vaccine will ever develop the ability to have longer term immunity, or is there immune response forever altered by the vaccine? (I have natural immunity and accepted isolation and discrimination rather than taking the vaccine)

The lack of long-term effectiveness of mRNA vaccines is a feature, not a bug. It’s much more profitable for Big Pharma to have a never ending stream of required boosters instead of a vaccine that is effective in the long-term.