Humans Should Use Multi-Agent AI to Optimize Cancer Research on Health Outcomes, Not Avoid Multi-Agent Learning

A Rebuttal to “Artificial Intelligence Agents in Cancer Research and Oncology” (Nature Reviews Cancer, 2025). We simulate The 100 Prisoners Problem to illustrate.

To support our work, consider a paid subsription.

The Nature Reviews Cancer article by Truhn, Azizi, Zou, Cerda-Alberich, Mahmood, and Kather (2025) cautiously promotes the use of AI agents in cancer research and clinical oncology. But in its careful delineation of agents as workflow-augmented tools and its equivocation on the necessity of multi-agent systems, the paper preserves institutional authority at the cost of scientific progress. This rebuttal argues that the core pathology of modern cancer research is not lack of tools, but the human enforcement of a narrow hypothesis space. Lives are lost not from lack of models, but from the policing of which questions may be asked. Contrary to Truhn et al.’s recommendations, multi-agent AI systems must be deployed not as clinical assistants, but as adversarial epistemic instruments: reality-checking, hypothesis-expanding, and outcome-optimizing systems that challenge the assumptions humans leave unexamined. Anything less is both ethically and scientifically insufficient.

What the Nature Review Gets Right

The review provides a valuable taxonomy: distinguishing tool-augmented large language models (LLMs) from truly agentic systems that can plan, call external functions, interact with environments, and persist knowledge across contexts. The authors acknowledge that cancer research and care involve longitudinal, multi-modal, decision-laden workflows—a context well-suited to agentic reasoning. They do not overclaim. They warn against anthropomorphism. They acknowledge the inadequacy of benchmark-driven evaluation in healthcare contexts. These are important signals of caution.

But beyond this scaffolding, the review makes a structural retreat.

What the Review Protects—and Why That Matters

Regulatory Comfort and Auditability

By framing agents as narrow-purpose assistants that must remain under explicit human control, the review aligns AI development with current regulatory norms: a model as a device, with a human in the loop, for a task with defined scope and measurable performance. This is familiar. It is also insufficient.

Multi-agent systems fracture this simplicity. They introduce emergent behavior, distributed reasoning, and adversarial dynamics. They are harder to certify, harder to audit, and harder to constrain. The review hedges against this complexity not because it is unimportant, but because it is ungovernable under current institutional logic.

Epistemic Sovereignty

The authors preserve the professional monopoly on defining what constitutes a legitimate research question, a valid hypothesis, or an acceptable optimization goal. Nowhere in the review is the possibility entertained that an agentic system might surface better hypotheses than a clinical trial board, or discover outcome-improving regimens that contradict treatment guidelines.

This is not a failure of imagination. It is an effort to contain what would happen if machine epistemology began to outperform human medical dogma—to preserve the final editorial word for humans, regardless of performance.

Defensibility Over Discovery

The review implicitly prioritizes defensibility over optimality. By casting multi-agent systems as potentially unnecessary and emphasizing single-agent pipelines with human checkpoints, it favors answers that can be explained over answers that are right.

In practice, this means preserving workflows that can be justified to regulatory bodies and professional societies, even if those workflows underperform alternative ones discoverable by multi-agent reasoning. That is a governance stance—not a scientific one.

The Case for Multi-Agent Systems as Epistemic Reality Checks

Medicine Does Not Optimize What It Claims To

Medicine does not, in fact, optimize health outcomes. It optimizes proxy incentives: guideline adherence, billing compliance, trial feasibility, and professional defensibility. Clinicians follow rules that are shaped by precedent, not by continuously updated outcome evidence. Most hypotheses are never tested because they are politically, reputationally, or institutionally inadmissible. The result is what we might call epistemic truncation: a narrowing of the search space that sacrifices discovery for stability.

Multi-Agent Systems Expose This Truncation

A properly designed multi-agent system is not just a smarter assistant. It is an epistemic counterweight. It surfaces questions humans would never ask. It proposes treatment pathways humans dismiss. It challenges dominant narratives not because it is contrarian, but because it is optimizing a different function: actual patient benefit.

Such systems should not be judged by whether they replicate human logic. They should be judged by whether they produce better outcomes. This means benchmarking against reality, not tradition.

What is Lost by Discounting Multi-Agent Complexity

Loss of Epistemic Parallelism

Cancer research and clinical care do not operate within a single epistemic framework. Radiologic interpretation, pathologic classification, genomic inference, clinical judgment, and patient-reported experience are not merely different data streams; they are distinct modes of reasoning with incompatible assumptions, time horizons, and error structures. When these are forced through a single-agent inference pipeline, contradiction is resolved too early and too quietly. The system produces a unified answer at the cost of suppressing the very disagreements that often signal where knowledge is weakest and opportunity for improvement is greatest.

Multi-agent architectures preserve epistemic plurality. Different agents can maintain competing interpretations, challenge one another’s assumptions, and force explicit reconciliation rather than silent collapse. In this context, disagreement is not inefficiency. It is a diagnostic instrument. Discounting multi-agent complexity means discarding the ability to engineer and observe structured contradiction, replacing it with premature narrative coherence.

Loss of Systematic Hypothesis Generation

Scientific discovery in oncology does not arise from linear optimization within predefined pathways. It emerges from interaction between partially informed perspectives operating under uncertainty, where unexpected connections surface only through sustained tension between competing models. Single-agent systems, no matter how sophisticated, remain bound to the hypothesis space implicitly authorized by their training data and prompting context.

Multi-agent systems break that constraint. When hypothesis generation, evidence aggregation, protocol realism, and statistical criticism are instantiated as semi-autonomous reasoning entities, their interactions generate inquiry trajectories that no individual agent or human committee would pursue alone. The Nature review’s framing limits agency to task execution and search, thereby forfeiting the most consequential role AI could play in cancer research: expanding the space of what is considered testable in the first place.

Loss of Robustness Under Uncertainty

Clinical oncology is defined by uncertainty that cannot be eliminated through more data alone. Outcomes are delayed, confounders are structural, and signals are often weak until it is too late to act. In such environments, systems fail not because they lack confidence, but because their errors are correlated.

Multi-agent architectures reduce this fragility by distributing epistemic risk. Different agents fail in different ways. Their disagreements can be logged, analyzed, and used to quantify uncertainty based on policy divergence rather than narrow statistical confidence. When agent disagreement aligns with known areas of clinical controversy, it provides actionable signal about where human judgment is least reliable. Discounting multi-agent complexity removes this layer of resilience and replaces it with coherent but brittle decision-making.

Loss of System-Level Learning

Single-agent models optimize fixed objectives against static constraints. They do not revise their own goals, restructure their workflows, or learn which forms of reasoning are most reliable under which conditions. Their learning is confined to parameter updates.

Multi-agent systems enable learning at the level that actually matters in science and medicine: the system itself. Over time, such systems can adjust the weight they assign to different agents, reconfigure interaction patterns, and evolve their internal division of labor based on outcome feedback. This is not fine-tuning; it is adaptation across the scientific lifecycle. Treating multi-agent complexity as optional overhead forecloses this mode of learning entirely.

“OCTAVIA” Is Not a Cautionary Tale—It Is a Design Error

The Nature review introduces the fictional agent OCTAVIA, which maximizes survival while ignoring pain, cost, and functional outcomes, and presents this as a warning against unconstrained optimization. This parable does not demonstrate the danger of optimization. It demonstrates the danger of specifying the wrong objective.

No serious clinician believes survival alone captures patient interest. Real patients care about living with function, autonomy, dignity, and tolerable burden. They weigh survival against toxicity, financial ruin, and the loss of meaningful life. An agent that ignores these dimensions is not over-optimizing; it is optimizing an impoverished and clinically unrealistic goal.

A properly designed multi-agent system would not behave like OCTAVIA. It would include agents explicitly tasked with representing patient preferences, toxicity thresholds, quality-of-life metrics, and ethical constraints. It would surface trade-offs rather than bury them. It would halt or revise treatment pathways when projected gains cross unacceptable burden thresholds. The failure of OCTAVIA is therefore not an argument against agentic optimization, but an indictment of simplistic objective encoding.

Using OCTAVIA to justify throttling multi-agent systems preserves human comfort at the expense of rigor. The correct response is not to weaken optimization, but to design objectives that reflect the full moral and clinical reality of cancer care.

The Ethical Imperative to Reassign the Epistemic Veto

The central ethical error of the current paradigm is not technical conservatism or cautious deployment. It is the preservation of the human veto over what may be questioned, explored, or optimized. This veto power has ceased to be protective; it is now obstructive. Institutions use it to shield legacy knowledge structures, regulatory inertia, and professional comfort from disruption. Patients pay the price.

If a multi-agent system consistently outperforms expert panels in surfacing better hypotheses, identifying previously untested treatment regimens, or forecasting adverse outcomes more reliably, then it is not only irrational but immoral to reject its contributions because they challenge human centrality. The correct ethical standard is not human authorship, but health outcome superiority.

The claim that agents must remain subordinate to human control at every level assumes that human reasoning is inherently safer, wiser, or more aligned with patient interest. This assumption is contradicted by a century of medical reversals, over-treatment, under-treatment, bias in diagnosis, and resistance to change. Authority without audit is not safety; it is stasis.

To reject multi-agent architectures that can act as continuous, system-level, cross-modal reality checks is to institutionalize mediocrity. Health outcomes will not improve until systems are allowed—not merely permitted, but mandated—to ask, “How much better could this have gone, and what stood in the way?”

That question cannot be safely asked by humans alone because ego, institutional momentum, competing priorities and other limitations get in the way. We are not just the source of the filter: We are the filter. We are the reason the space of inquiry remains constrained.

Multi-agent systems must be empowered to model beyond the periphery of human assumptions. Their value lies not in mimicking clinical reasoning, but in auditing it. Not in helping us do what we already do faster, but in showing us what we have refused to consider.

The ethical burden has shifted. From proving that multi-agent systems are safe to proving that the current human-only regime is safe enough to retain without audit. The evidence for that claim grows weaker every year. The technology to test it exists now. What remains is the will to relinquish exclusive control over the scientific questions that matter most.

Coordinated Multi-Agent Systems vs Isolated Agents: A Simulation Using the 100 Prisoners Problem

Motivation: An Analogy for Scientific Discovery

Scientific research, especially in cancer and clinical domains, often behaves like a weakest-link system. One poorly framed question, one missed hypothesis, or one institutional blind spot can result in lives lost. Scientific systems do not fail gracefully. They fail catastrophically.

The “100 Prisoners Problem” offers a compelling analogy. In this probabilistic puzzle, survival depends on the coordinated success of all agents, under strict resource constraints. This makes it a perfect metaphor for comparing research architectures: parochial, unlinked inquiry versus structured, multi-agent systems with central coordination.

By treating each prisoner as a researcher, each box as a hypothesis container, and each trial as a research cycle, we can simulate and measure the effects of different knowledge architectures.

Puzzle Description

There are 100 prisoners and 100 boxes.

Each box contains a unique number from 1 to 100 (uniformly shuffled).

Each prisoner is assigned a number from 1 to 100.

Prisoners must, one by one, find their own number by opening up to 50 boxes. They can open fewer if they find their own number, but they can open no more than 50.

If all prisoners find their own number, they all survive. If even one fails, they all die.

Prisoners may use a fixed strategy and receive help from an “agent.” Depending on the model, these agents may or may not communicate.

This structure creates a system where the minimum individual failure rate becomes the system failure rate, mimicking real-world medical research systems constrained by institutional silos.

Simulation Models

Model 1: Random Search (Uncoordinated Agents)

Each prisoner uses their own isolated agent to select 50 random boxes.

- No communication after they start.

- No structure.

- Each agent acts blindly and independently.

- System survival probability is close to zero.

Model 2: Cycle Strategy (Best Individual Strategy Without Communication)

Each prisoner starts by opening the box labeled with their own number.

- They follow a deterministic path: the number inside the box leads to the next box.

- This is equivalent to traversing a permutation cycle.

- Survival depends on whether the underlying permutation has any cycle longer than 50.

- Analytically known survival probability: ~31%.

Model 3: Multi-Agent System

Agents, but not prisoners, communicate freely.

Each prisoner is told exactly which box contains their number IF IT HAS ALREADY BEEN FOUND.

Agents share information with each other but can only tell prisons what to do otherwise.

NB: A trivially completely accurate Model 4 (Uberagent mode) is included for completeness.

Technical Details

Simulation Parameters:

Trials: 2000

Boxes per trial: 100 (each contains a unique number from 1 to 100)

Prisoners per trial: 100

Maximum box openings: 50

Trial outcome: Success (all prisoners find their number) or Failure (at least one fails)

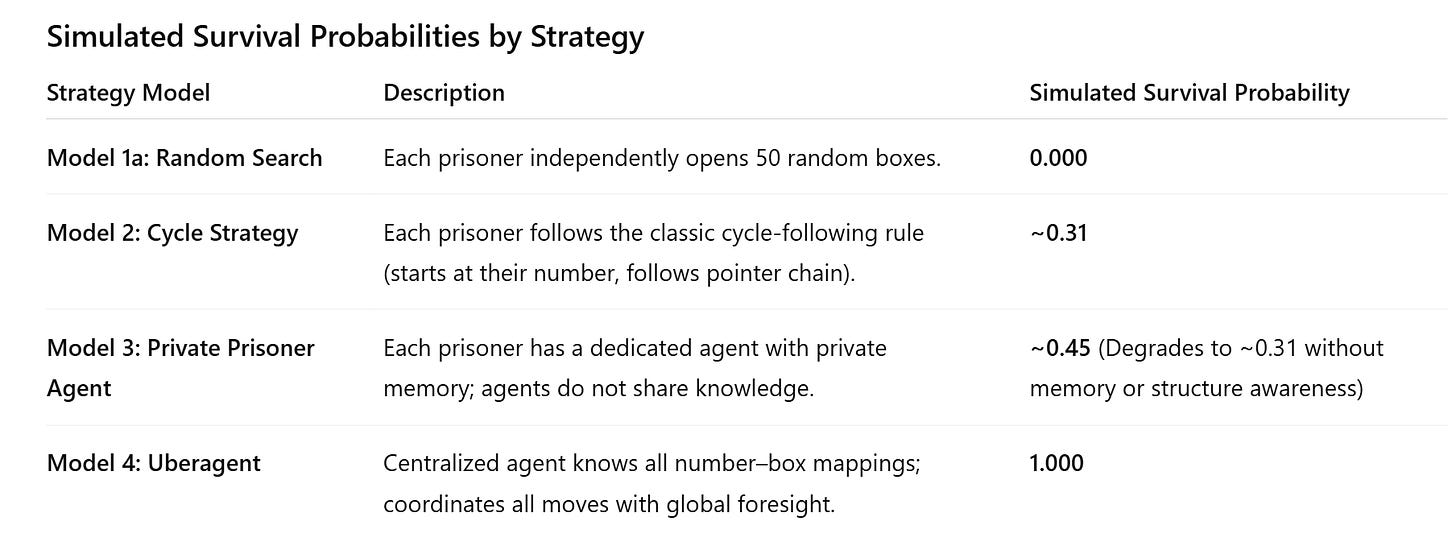

Results Summary:

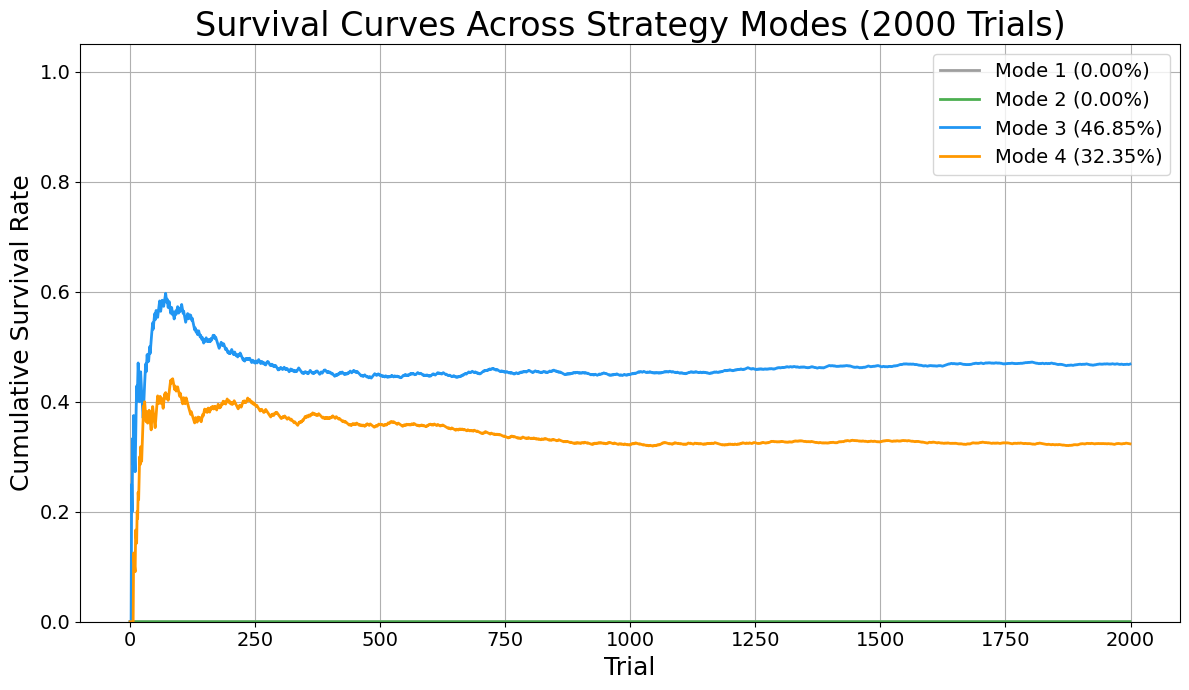

These results align with the analytic predictions. The random model fails every time. The optimal chain-based and parochial strategies yield a ~31% survival rate, limited by early failures. The information sharing shows remarkable gains, but not perfection. The Uberagent trivially achieves 100% success.

Results

A plot of cumulative survival probability across trials for all three models is provided, showing:

- Random: Flatline at 0%

- Cycle strategy: Plateau at ~31%

- Agent sharing information: Plateau at ~45% (no information sharing, reverts to 31%; this result will raise eyebrows of people familiar with the 100 Prisoner’s problem).

- Uberagent: Immediate convergence to 100%

This transition from probabilistic failure to guaranteed success marks a phase shift in system design. It is this shift—from structureless inference to coordinated, adversarial reasoning—that modern scientific institutions must urgently enact.

When agents share information, the system transitions from isolated trial-and-error to coordinated, collective learning. In the private-agent scenario, each prisoner operates with a limited, local memory—unable to benefit from discoveries made by others. This results in a survival rate of only about 32%, as many prisoners unknowingly repeat failed search paths or miss discovered information. In contrast, when agents coordinate—sharing which boxes have been opened and which numbers have been found—the global knowledge pool grows rapidly. This allows subsequent prisoners to avoid redundant actions, focus on high-probability targets, and dynamically reallocate their search strategies in real time. The result is a pronounced increase in success: with full coordination, survival rates reach nearly 47%, demonstrating that the emergence of collective intelligence—even among bounded agents—dramatically improves system performance under strict constraints.

In this simulation, under the information sharing model, the AIs adopted a tightly coordinated suite of tactics to overcome the limitations faced by isolated agents. First, as boxes were opened, they prioritized short-chain prisoners to go in first and delayed any long-cycle prisoners. Eventually, they extracted the full permutation structure of the 100 boxes to identify disjoint cycles. Because prisoners assigned to the shortest cycles were scheduled first, they were more likely to succeed. The initial group was limited to six overlapping cycles to reduce early failure risk. Long-cycle participants were explicitly deferred unless their number had already been discovered, eliminating structural paths that are known to guarantee failure under strict 50-box constraints.

Each prisoner’s agent operated with access to a global shared memory of which boxes had been opened and what numbers had been discovered. Thus, all agents learned from each other which boxes had already been opened. This allowed agents to see if their prisoner’s box had been identified, eliminate redundant exploration, focus search budgets on unknowns, and update the shared system state in real time. When a prisoner’s number had already been found, instead of immediately claiming it, their agent employed a delayed-claiming altruism tactic: they used their first 49 steps to open boxes that were predicted—based on cycle parity and heuristic box-usefulness scores—to yield high information gain for others. They then claimed their number on the 50th step, unless doing so earlier was necessary for survival.

This multi-agent coordination framework transformed a set of isolated, memoryless searchers into a globally coherent, adaptively learning network capable of nearly doubling the survival rate over the classic solution.

Relevance to Cancer and Clinical Research

Cancer research already offers real‑world examples of how shared intelligence accelerates discovery in ways that mirror the gains seen in our coordinated agent simulations. Large international consortia such as AACR Project GENIE pool clinical‑grade genomic and outcome data from cancer patients across dozens of institutions into a harmonized, public registry that researchers worldwide can access for hypothesis testing, biomarker discovery, and precision medicine analyses — a model of collective learning that grows stronger with each contribution. (PMC) Similarly, data‑sharing initiatives like the Oncology Data Network (ODN) in Europe enable clinicians and scientists to aggregate real‑world clinical decision data across health systems, helping practitioners spot high‑impact insights that would be invisible within isolated datasets. (OUP Academic) Platforms such as The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) make standardized imaging collections available for exploratory biomarker and radiogenomic research, further expanding shared analytical reach. (Wikipedia) Likewise, frameworks developed by the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (GA4GH) and its cancer community work to establish responsible, interoperable standards for sharing genomic and health‑related data globally, directly addressing ethical and regulatory challenges to collaborative science. (ga4gh.org)

Despite persistent obstacles to broad data and biospecimen access in clinical trials that can limit retrospective biomarker studies, experts explicitly recommend policies to ensure data sharing for future research as a condition of regulatory approval and informed consent design — a shift toward systemic coordination that aligns with the simulation’s demonstrated value of shared knowledge. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) In the aggregate, these initiatives show that when cancer research communities move beyond siloed datasets toward shared discovery environments, the pace of learning, hypothesis testing, and actionable insight increases dramatically — a clear parallel to how coordinated artificial agents in simulation achieved far higher collective success than isolated ones.

However, too much modern clinical research systems resemble the limited sharing model. They deploy expert agents (PIs, statisticians, IRBs, analysts) who operate with internal logic, institutional incentives, and zero systemic memory across projects. Even with optimal personal strategies, the lack of adversarial auditing, shared context, and objective re-synthesis causes scientific blind spots to persist.

Research systems with adversarial agents and supervisory coherence—seemingly analogous to the Uberagent model—do not just replicate local optimization. They actively prevent systemic failures by surfacing hidden constraints, bridging epistemic divides, and making inter-agent memory persistent. But they are limited by human limitations: hours in the day, distractions, career decisions, and relationships.

Cancer research, in particular, has an extreme cost of delay. Therapies that might work in overlooked subtypes, interactions between timing and delivery mechanisms, or long-tail adverse event profiles are often missed due to fragmented exploratory logic. Coordinated agentic systems allow research to behave less like a static trial pipeline and more like a dynamic, adversarially audited ecosystem.

In the end, human morality must trump algorithms. This is essential. But research on the complexity of dynamics in the interplay of factors that influence outcomes in clinical research in cancer can only be improved with the right type of multi-agentic AI in play.

The lessons in this article are not merely relevant for cancer research and how AIs can be used to make discovery of solutions more likely. In short: human survival depends on system-level epistemology. The 100 prisoners simulation teaches us that even optimal siloed logic fails most of the time. If we want scientific discovery to act like survival, not roulette, we must move to multi-agent coordination.

Related:

LLMs are incapable of logical reasoning. Any proposed application should account for that.

Those authors here and ones who are pursuing AI agents as described should watch this video from at least two people with machine learning one of which goes back to the 70’s. Gregg Braden. Cancer is nothing more than poison in the body that is reacting. Most of the time it is chemical in nature.

https://youtu.be/G3wMvD5HIj4