Can Consciousness, Logic and Reason Exist at Planck Time Awareness?

How brief is an “instant”? What constitutes “now”? How did mother nature choose the timeframe in which we perceive reality? Given the limitations of our biology, we literally live in the past.

How brief is an “instant”? What constitutes “now”?

Imagine a bee buzzing near your nose, its wings flapping at a speed almost too fast for the human eye to follow. Now, let's venture into a fascinating and radical thought experiment that intersects both physics and philosophy.

Firstly, let's consider the time scales.

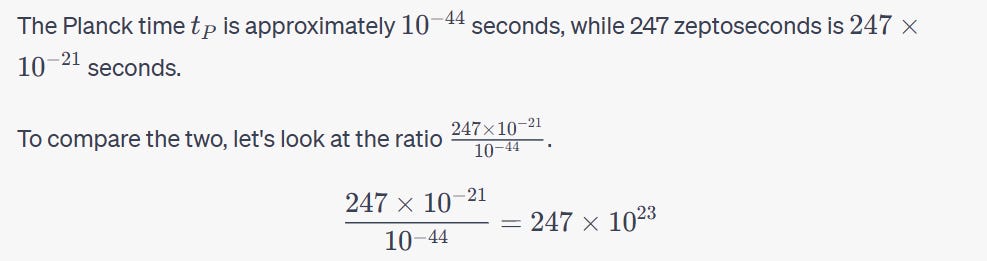

The Planck time is a theoretical lower limit on the divisibility of time, based on fundamental constants of nature. The shortest period of time ever measured to date is 247 zeptoseconds.

This number is astronomically large, indicating that 247 zeptoseconds is vastly greater than the Planck time.

The 247 zeptosecond time period is unimaginably longer than the Planck time. This is a huge difference, highlighting the minuscule nature of the Planck time in comparison to even other minute time scales.

How These Extreme Scales Interact with Our Understanding of Reality

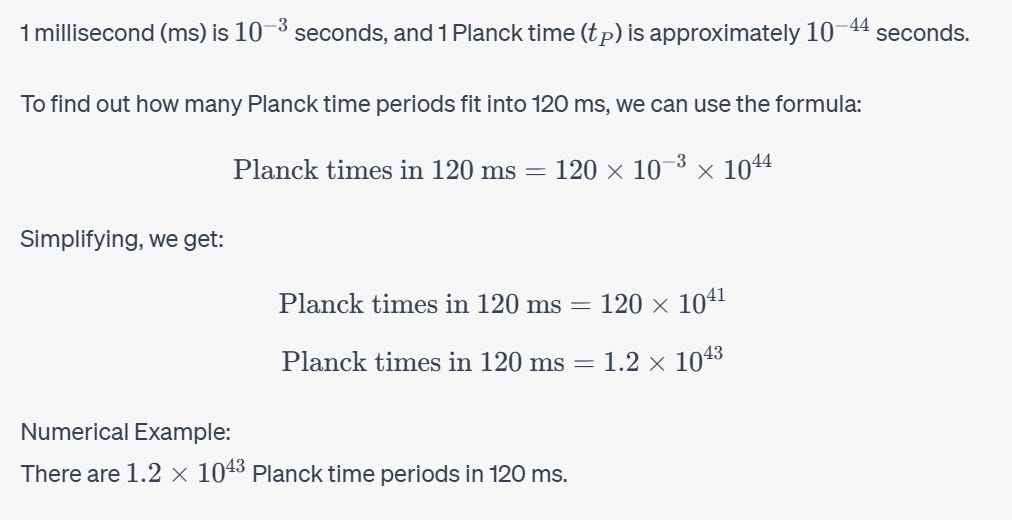

We perceive senses 120 ms after they hit our organs of perception.

If a consciousness could perceive and react to stimulus in two Planck moments, the stimulus/response cycle would be

This is a realm where our usual notions of time and perception are not just stretched but are fundamentally altered.

Temporal Perception

In our universe, where the fastest known interactions—like the speed of light—occur on the order of nanoseconds (10^-9 seconds) or slower, a consciousness operating on the Planck time scale would perceive the universe as almost entirely static. Nothing would appear to move. Even the fastest quantum transitions would appear to take an "eternity" for such a being.

Information Processing

The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle imposes a fundamental limit on the precision with which certain pairs of physical properties can be simultaneously known. At the Planck scale, the uncertainty would be so significant that it is unclear how meaningful "sensing the world" could be.

Causal Paradox

In classical physics, cause precedes effect. However, at the Planck scale, the very notion of "before" and "after" becomes fuzzy due to quantum gravitational effects. This fuzziness could lead to paradoxical situations for a consciousness operating at this scale; it seems unlikely that consciousness as we understand it could exist operating at Planck-time speed.

Energy Requirements

The energy required to perform computations at this scale would be astronomical. According to the Margolus-Levitin theorem, the minimum time

to perform a computation is bounded by

where

is the energy used and

is the reduced Planck constant. To operate at Planck time scales, the energy requirements would be so enormous that they would likely form a black hole, according to general relativity.

Perception

To put this into perspective, let's consider a typical human reaction time of about 0.25 seconds. A consciousness operating at 2 times the Planck moment seconds would experience one human "moment" as:

That's practically infinitely times longer than their own "moment," making our fastest reactions seem eternally slow.

The Time-Perceiving Brain

Now, let's add another layer of complexity to our thought experiment. Imagine a being with a dual-brain system—one that operates at the Planck-time scale and another that perceives time at the same stimulus-response cycle as humans. This second brain would serve as a temporal bridge, allowing the being to be "aware" of the almost infinite moments that pass between what we humans would perceive as two adjacent points in time.

This dual-brain system introduces a paradox of perception. On one hand, the Planck-time brain would perceive the universe as almost entirely static, while the human-time brain would experience the flow of time as we do. There are two configurations we can explore.

The interaction between these two brains would create a unique form of consciousness, one that can perceive both the "eternal now" and the flowing river of time, or

The interaction between these two brains would create a unique form of consciousness, one that merely register each infinitesimally small moment as it passes, and that information is accessed as a memory by the time-perceiving brain.

Think about the limitations of our own perceptions and the vastness of the universe's complexity. This exercise tells us that our biology - our ability to perceive - is tuned to the “meaningful” and “relevant” information from our environment. We cannot adapt or react to information we cannot perceive.

We Could Handle the Second Configuration, but Suffer from Miserably from Information Overload

Reality itself is, thankfully, largely information preserving - that is, as long as we perceive the consequence of events that occur faster than our ability to perceive, we can operate reasonably well. Any information that persists from Planck reality that persist long enough for our intolerably slow information processers to perceive, we are able to infer what has happened over the last 120 ms.

Like the massive amount of energy, however, a second brain would cause the time-perceiving brain to be overloaded with sorting and prioritization tasks. This means it would have to ignore nearly all of the stored information. The cost would be prohibitive and wasteful. Natural selection operates on efficiency; our own brains ignore massive quantities of information they receive as it is.

While the notion of a Planck-time consciousness may seem like the making of science fiction, it serves as a useful tool for exploring the boundaries of what we know and what we have yet to discover. In the words of William James, "The deepest thing in our nature is this benthic layer of the unknown." And so, like the bee that buzzes too quickly for our eyes to follow, the mysteries of consciousness and time continue to elude us, inviting us ever deeper into the enigma of existence.

This article does wonders for my racing thoughts.

Kozyrev wrote extensively on the nature of time.